2020 Legislative Priorities

Syringe Service Programs (SSPs)

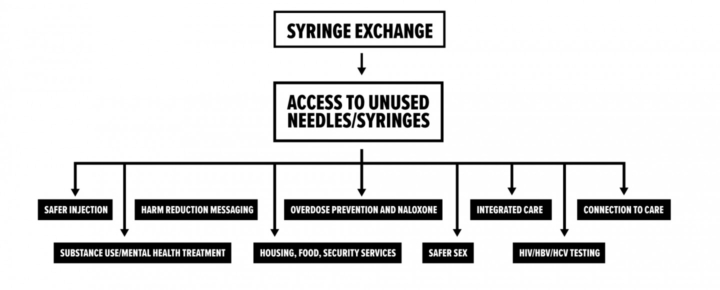

Syringe service programs (SSPs), also known as syringe exchange, needle exchange, or syringe access programs, are an evidence-based strategy to reduce infectious disease transmission by providing people who use drugs with sterile needles and syringes and facilitating safe disposal of used ones. SSPs also provide other services such as testing for HIV and hepatitis C, overdose prevention education, referral to drug treatment programs, tools to prevent HIV and other infectious diseases (such as condoms, counseling, or vaccinations), and linkage to medical, mental health, and social services. Research on SSPs across the U.S. over the past 30 years has shown a number of additional benefits.

Overview

The evidence shows that syringe service programs…

- Decrease rates of infectious disease transmission

- Decrease overdose fatalities (including opioid overdose)

- Decrease financial costs related to drug use

- Increase entry into drug treatment programs

- Increase the number of individuals who enter and maintain recovery from substance use disorders

- Increase public safety by reducing syringe litter and reducing accidental needlestick injuries to the public, law enforcement, and waste management.

Syringe service programs are currently illegal in Iowa. Under Iowa’s drug paraphernalia code, possession or distribution of needles and syringes for the purpose of illicit drug use is classified as a simple misdemeanor.

Since 2017, a diverse group of stakeholders has supported a bill that would legalize SSPs by modifying this code. To allow authorized SSPs to distribute needles and syringes and individuals to possess needles and syringes that they obtained through an SSP.

We understand that providing needles to people who use drugs may seem like a counterintuitive approach to addressing drug use. In a perfect world, no one would struggle with drug addiction. All people would feel happy, comfortable, and free from pain and suffering without the use of psychoactive pharmaceutical agents. IV drug use, chaotic drug use, substance use disorders, and addiction wouldn’t exist, and there would be no need for syringe service programs. However, we can all recognize that we have a long road ahead of us to get to this ideal future. In the meantime, SSPs can support people in our community who are struggling and prevent as much illness and suffering as possible.

SSPs have existed in the U.S. since the late 1980s. They are supported in a wide range of communities across America, from rural to urban, conservative to liberal, deep South to New England, and Midwest plains to the coasts. The Surgeon General and the CDC support syringe service programs for all 50 states – Read on to learn why.

Our vision for an ideal future and a better Iowa is one in which problematic drug use is virtually non-existent: upstream causes of addiction are addressed, and when they do occur, substance use disorders (SUDs) are treated quickly and effectively.

To create the healthiest possible Iowa, many years of work lie ahead of us. In the interim, we can make sure that people who develop SUDs encounter as little harm as possible. Through the services that SSPs provide, we can make sure that no person who is struggling with drug use will contract HIV. We can put a stop to deaths due to accidental overdose. We can end the need for costly liver transplants (a potential outcome from hepatitis C viral infection).

Syringe service programs are analogous to a boat that has sprung a leak: It is important to ensure that everyone in the boat puts on a life vest or flotation device while everyone is simultaneously working to repair the leak and drain any water that the boat takes on.

The services provided by a SSP are similar to the life vest: they make sure that no one drowns while they are working to fix the boat, or that no one dies while experiencing a substance use disorder. The SSP is also the bucket that is scooping up the excess water – it helps make sure that any harms that do arise cause as little damage as possible. And, the SSP is also a lifeboat: it steps in to help the boat make it to shore and guide the boat to safety. In this same way, SSPs help to guide people with SUDs to treatment, housing, employment, or medical care in order to improve access, engagement, and retention.

Table of Contents

- The Problem: Twin epidemics – Opioid use and infectious disease in Iowa

- The Big Picture: De-stigmatizing substance use disorders

- The Data: Exploring the evidence on SSP efficacy & impact

- The Bill: Proposed legislation and its history

- The Costs: Funding & Implementing SSPs

- The Context: SSPs around the U.S.

- The Supporters: Iowa law enforcement endorse SSPs

- Take Action: Advocate for legal syringe access

The problem: Twin epidemics - Opioid use & infectious disease in Iowa

Iowans struggling with addiction are becoming sick and dying of infectious disease. Iowa is currently in the midst of multiple epidemics, with a dramatic rise in drug use (particularly heroin use and meth use) fueling a parallel increase in viral infections. Multiple (or twin) epidemics that occur simultaneously and are interconnected are labeled as a “syndemic.” Iowa’s current syndemic began shortly before 2010 with the emergence of the opioid overdose crisis. As prescription opioid use gave way to heroin use, Iowans increasingly utilized needles as the preferred route of administration for heroin. The acceleration in IV heroin use gave rise to an epidemic of viral hepatitis C infections. This situation was not improved upon by trends in methamphetamine use around the state: Iowans are using meth in greater numbers, and injection is increasing as a preferred route of administration among people who use meth. A recent study from the country’s leading infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, notes that injection drug use is increasing quickly particularly in rural states. But, problematically, only 1 in 4 people who use IV drugs are estimated to have access to a source of sterile syringes.

Drug Use in Iowa:

In 2017, there were 206 overdose deaths involving opioids in Iowa. The greatest rise occurred among heroin-involved deaths, which more than quadrupled from 14 deaths in 2012 to 61 deaths in 2017. Deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (mainly fentanyl), rose threefold from 29 cases in 2011 to 92 cases in 2017. Since 1999, prescription opioid-involved deaths steadily rose to a peak of 132 in 2012, but since then, they have declined by 20 percent to 104 cases in 2017.

While opioids have dominated the news for the past decade, meth has long been the more popular drug in Iowa. From 2014-2017, there was a 38 percent increase in methamphetamine treatment admissions in Iowa. Similarly, the Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) reports there was an eight-fold increase in Iowa deaths related to amphetamines, which includes methamphetamine. Meth is now the second most commonly used drug in Iowa, surpassing marijuana in 2019 but trailing behind alcohol.

While it might be assumed that people use one drug exclusively, the use of multiple drugs in combination is common and becoming more popular in Iowa. This is referred to as poly-drug use and involves the use of multiple substances over the course of a day or week, not necessarily at the same moment. Among participants in Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition’s program (a set of services that can be best understood as a precursor to a SSP), the following drug use trends emerged from January – June 2020:

- 65.1% use meth

- 51.2% use heroin

- 26.5% use prescription opiates (not prescribed)

- 26.0% use cocaine

- 9.8% use crack

- 12.1% use benzodiazepines (eg. xanax) (not prescribed)

- 23.3% use other substances not listed here (not including alcohol)

Infectious disease in Iowa related to drug use:

When unable to obtain sterile needles and syringes, it is common to re-use old needles and/or share previously used needles. Both sharing and re-using lead to the transmission of a number of viral and bacterial pathogens. This in turn leads to the development of infectious diseases that are deadly and costly. These include but are not limited to viral illnesses like HIV, hepatitis C, as well as bacterial diseases such as endocarditis, sepsis, bacteremia, abscess, and cellulitis.

- Hepatitis C is a viral infection that damages the liver and can ultimately cause liver failure and death. It is a common cause of liver cancer and sometimes contributes to the need for liver transplantation.

- Unlike the other viruses that attack the liver (hepatitis A and hepatitis B), there is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

- Hepatitis C is the number one killer among infectious diseases in the nation, killing more than the next 60 leading infectious diseases combined. (Data is from prior to COVID-19).

- Injection drug use is the primary risk factor for viral hepatitis C (HCV) in the United States. Injection drug use accounts for 68% of all new infections. A 2017 report from the CDC warned that the opioid crisis is the key driver of the explosive increase in HCV infections.

Recently, Iowa has experienced a significant increase in rates of hepatitis C infection. From 2000 to 2015, the number of Iowans diagnosed with hepatitis C nearly tripled. As of 2015, there were 21,748 Iowans diagnosed with hepatitis C.

- HIV is a virus that damages the immune system. When the immune system becomes severely damaged by the virus, the infection progresses to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). At this point, the immune system cannot protect the body, and the person may die.

- As of December 2019, there are 2,938 Iowans known to be living with HIV. 14% of these people report having used injection drugs.

- A warning: In 2017, the CDC notified Governor Reynolds that Iowa is at risk of a HIV outbreak due to the state’s recent increase in IV drug use, hepatitis C cases, and overdose deaths. The situation in Iowa is much like the situation that foreshadowed an outbreak of new HIV cases in Scott County, Indiana in 2015:

- A cautionary tale

- Much like Iowa: Scott County, IN is a county like many of Iowa’s counties along the Missouri border. In 2019 the county’s population was just under 24,000.

- A rare illness: HIV was previously exceptionally rare in Scott County. Between 2004 and 2013, there were 5 HIV infections reported in the county. SSPs were illegal in Indiana, and none operated in Scott County.

- The outbreak: Between November 2014 and November 2015, there were 181 new cases of HIV. Almost 90% of these cases were linked to injection drug use. By the end of the outbreak, 235 cases were documented.

- A warning: This outbreak of HIV functioned as a national alarm, warning communities around the U.S. that the opioid crisis was giving birth to multiple other epidemics (syndemics), and that many communities might expect to see a rise in HIV cases as IV heroin use increased in communities where syringe exchange programs were illegal or nonexistent.

- The impact: At the time of the outbreak, the CDC Director Tom Freidan observed that Scott County had one of the highest rates (for its population size) of anywhere in the world. Aside from the impact on human health and the lives of the people who were impacted, the impact on state, local, and federal healthcare systems is immense: it is estimated that the lifetime cost to treat HIV for all 235 individuals will exceed $260 million.

- Never again: A 2019 study from Brown University found that if a syringe exchange program had been established prior to the outbreak, 90% of the HIV cases would have been prevented.

Read on to learn more about Indiana’s response to the crisis.

Ever since the 2015 outbreak of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Scott County, Indiana, it has been clear that the sharing of syringes among people who inject drugs is fueling the spread of these diseases in rural America.

- Many bacteria live on our skin that are normally harmless to us. However, when these bacteria get under the skin or into the blood (by injecting with a non-sterile needle or injecting through skin that wasn’t properly cleaned first), they can cause serious infections.

- Skin and soft tissue infections (such as abscess & cellulitis)

- Abscesses occur when an infectious agent (usually Staphylococcus aureus, which lives on the skin) is introduced under the skin. In response to the infectious agent, the body mounts its defenses and forms a mass full of pus and debris under the skin. Abscesses are very painful and require prompt treatment with antibiotics. If not treated early, they may require surgery to drain the wound.

- Cellulitis is an infection of the deeper layers of the skin, usually caused by group A Streptococcus, which normally lives on the skin but is dangerous when introduced beneath the skin. It appears as a red, swollen, painful patch on the skin. If not promptly treated with antibiotics, the infection can spread through the skin and even to the blood, bones, and heart, leading to serious illness and even death.

Skin and soft tissue infections are common among injection drug users without access to sterile injection equipment. One study of injection drug users in San Francisco found that nearly one-third of injection drug users had experienced skin or soft tissue infections.

- Bacteremia, sepsis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis

- Bacteremia occurs when bacteria gets into the bloodstream. From the bloodstream, the bacteria can travel to other places in the body and cause sepsis (a very dangerous immune response to infection), infectious endocarditis (infection of the heart valves), osteomyelitis (infection of the bone), and septic arthritis (infection of the joint).

Not only are these diseases deadly – they are costly. The estimated lifetime cost of treating HIV in an individual is $379,668. In 2013, approximately $6.5 billion was spent on treating hepatitis C infections in the United States.

The need is urgent

In December 2017, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) sent a letter to Governor Kim Reynolds notifying her that Iowa is at high risk for an HIV outbreak among people who inject drugs. Similar to the now infamous HIV outbreak of 2015 that took place in rural Scott County, Indiana, an HIV outbreak could impact the health of thousands of Iowans. There is an urgent need for action in order to prevent a public health catastrophe.

Read the letter from the CDC calling on Iowa to legalize syringe service programs

See news coverage summarizing CDC’s urgent warning

THE BIG PICTURE: DE-STIGMATIZING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Problems with our current narrative around drug use:

The story of addiction in America is that drug use is a personal and moral failure. People who use drugs lack will power and are selfish. We are told not to “enable” drug use. We are told to show our loved ones “tough love” by letting them suffer the consequences of their poor choices. But research shows that these approaches (and interventions rooted in such philosophy) don’t necessarily work. Part of the reason for this lies in the neurobiology of addiction, and the way in which psychoactive drugs interact with feedback loops in the brain’s reward system. As a result of the cognitive patterning in people experiencing SUDs, individuals continue to engage in or perpetuate drug use, despite negative consequences.

Conversely, a number of other chronic health issues result from sustained unhealthy behaviors. However, for persons who suffer from heart disease, types II diabetes, tobacco-induced cancers, or other illnesses with a behavioral component, we don’t turn our backs on them. We don’t tell them that they need to suffer the consequences of their poor choices in order to get better. Instead, we give them a compassionate care team who will educate them, help them make behavior changes to reduce their risks, and treat their disease. Why shouldn’t we do the same for the disease of addiction? Why don’t we meet people where they’re at and support them through another chance at a healthier life? This is exactly what SSPs are for.

A common point of debate: Do syringe service programs promote, encourage, increase, or enable drug use?

Providing needles to people who use drugs may seem counterintuitive, and these programs can appear to enable or promote drug use. For many people, intravenous drug use is something that they have little experience with, and it is a health issue that can feel remote from their day to day lives. Because of the stigma associated with addiction, it can be difficult to get a clear picture of what life is like for people who use and inject drugs. This also results in limited understanding or knowledge of how access to sterile needles and syringes may or may not impact an individual’s health behavior.

Although it can be difficult to understand, being handed a new needle or syringe does not have much influence on drug use among people who regularly use drugs (eg. if they will use drugs, when they will use drugs, how much they will use). Think of it like this:

You walk into a doctor’s office. The nurse hands you a brand new, empty, red plastic cup. What do you do with the cup? How do you decide what to use it for? Odds are, you aren’t going to high tail it to the nearest bar, fill the cup to the brim with liquor, and drink the contents as quickly as possible. Instead, you may save the cup for later or have a glass of water. You might also toss the cup aside, or hand it back to the nurse if you are not thirsty.

Like cups, needles exist simply to deliver a liquid into the body – albeit through a different path. For people who use drugs (and just as importantly, for people who do not), walking into a doctor’s office and receiving a sterile needle from the nurse does not inevitably result in drug use. The needle may be used for administering medication to a pet, taking insulin in the setting of diabetes, or fertility treatments. For people who do not use intravenous drugs / have not used needles in the past, the process of beginning to inject is complicated: public health researchers find that many people do not begin to inject drugs until 1-4 years after initiating use of heroin, methamphetamine, or cocaine, and often do so at first with the assistance of an acquaintance, friend, or intimate partner. IV drug use (IVDU) is extremely intricate and involves considerable skill. Thus learning to inject drugs may take a person anywhere from several months to several years. For those who do use IV drugs (PWID), it is most common to use a needle between 1 and 10 times per day, with an average of 2-4 times daily. The vast majority of PWID report that they will use drugs regardless of whether or not they have access to a new needle. This means that in order to maintain daily use, individuals will share syringes with another person, or re-use their syringes repeatedly. Both are dangerous and are associated with numerous viral and bacterial infections. Access to a needle is rarely a factor in whether or not one uses drugs on a given day or at a given time, with access to the drug itself being the crucial component.

The ideal story: a visit to an SSP

Rachel: A meth user who has struggled with her addiction for many years.

Lauren: An employee at the SSP who wants to help people in her community who want to help themselves, especially persons struggling with substance use disorder.

Rachel is a meth user who has struggled with addiction for many years. She’s not necessarily interested in any of the drug treatment programs in the state where she lives, but she also doesn’t want her drug use to progress further. Rachel learns that getting sterile syringes from an SSP can help her avoid contracting HIV or hepatitis C. She visits the local center and meets Lauren, one of the employees. Lauren isn’t judgmental. She is kind, compassionate, and understanding of where Rachel currently is with her drug use. She wants Rachel to feel comfortable returning to the SSP for help. The program’s goal is to have Rachel return here to seek opportunities for improving her wellbeing, which may include a substance use treatment program that is aligned with Rachel’s goals and needs.

Just like so many before her, Rachel is taking the first steps to helping herself.

Lauren provides Rachel not only with sterile needles but a full kit of supplies, complete with everything she would need to prepare and inject the drugs she uses. This is because hepatitis C is highly infectious and transferred through blood, which is found not only on needles, but also on other injection supplies like water, cookers, and cottons. Lauren also tells her that re-using her own syringes can cause bacteria from the skin to enter the bloodstream, leading to dangerous infections that affect the blood and heart. Lauren provides Rachel with a package of alcohol wipes and reminds her never to re-use her own syringes or share them with others. Lauren also provides her with naloxone (an opioid overdose reversal medication) in case she or someone she uses with overdoses. Finally, Rachel also learns more about how to avoid STDs and stay as healthy as possible.

At the end of the visit, Rachel feels more informed about her health and wellbeing. She now has a trusted source of information to turn to when she has questions and knows she won’t be judged. Before leaving, Lauren gives Rachel a small biohazard container and lets her know that she can bring back her used syringes to the SSP. She won’t need to worry about being arrested for paraphernalia because as long as she is a registered participant in the SSP, she will be permitted to return and dispose of her used syringes safely.

THE DATA: Exploring the evidence on SSP efficacy & impact

A 2014 meta-analysis of 12 studies found convincing evidence that needle- and syringe-exchange programs are associated with reductions in HIV transmission, and a 2017 Cochrane review suggested that a combination of syringe-exchange programs and opioid-substitution therapy could reduce the risk of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs. Along with the CDC, the American Medical Association, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine), and the World Health Organization all support syringe-exchange programs as important interventions that reduce the spread of infectious disease and can serve as gateways to obtaining naloxone, opioid-substitution therapy, HIV and HCV testing and treatment, and other medical care.

Research supports the benefits of SSPs to individuals and to communities. Click on the headings below to learn more about each research outcome.

People who get needles from SSPs are less likely to share or re-use needles

- In a Connecticut study on injection drug users before and after the implementation of new laws that removed legal barriers to purchasing and possessing syringes, researchers observed a 39% decrease in syringe sharing.

- In a Chicago study comparing people who inject drugs who went to an SSP versus those in an area without an SSP, the people who went to the SSP were 70% less likely to share needles.

In places where SSPs are implemented, rates of new HIV and hepatitis C infections decrease substantially

- Many studies have shown significant decreases in hepatitis C virus transmission following the implementation of SSPs. One study in Europe showed a 76% reduction in places with high coverage SSPs. Another study in the UK found a 59% reduction of hepatitis C virus transmission in areas with SSPs.

- In a meta-analysis of data from six high-quality studies on SSPs and HIV transmission, it was found that SSPs were associated with a 58% reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs.

Contrary to popular belief, SSPs do not increase rates of drug use. Often, they have the opposite effect.

-

-

- In a study on people who use injection drugs in Seattle, people who had participated in an SSP were 3.5 times as likely to stop injecting during the study than those who had never participated in an SSP.

- This same study showed that people who participated in an SSP were 3 to 5 times as likely to enter drug treatment than those who did not participate in an SSP.

-

Why do SSPs have this effect? It is hard to say for sure. Many of the participants in IHRC’s services want drug treatment, but face barriers to getting it – they don’t know how to get it, can’t afford it, or face long wait times to get into a treatment program. SSPs are able to connect people to treatment who might not be able to get it otherwise.

SSPs reduce the number of improperly disposed of needles

-

-

- In comparison of similar neighborhoods in San Francisco, CA (a city with SSPs) and Miami, FL (a city without SSPs), a study found:

- 8-fold more improperly disposed needles in the city without SSPs.

- 95% of injection drug users in the city without SSPs reported improperly disposing of their needles, versus 13% in the city with SSPs.

- In comparison of similar neighborhoods in San Francisco, CA (a city with SSPs) and Miami, FL (a city without SSPs), a study found:

-

SSPs reduce needlestick injuries in police and first responders

-

-

- In a survey of San Diego police officers, 29.7% had experienced at least one needlestick injury in their career.

- Fewer improperly disposed of needles means fewer needlesticks. Additionally, during police searches, people are more likely to tell the officer that they have a needle on them if they know that they won’t get arrested for it.

-

SSPs do not increase crime

-

-

- Several studies have found that there is no correlation between SSPs and crime, – that is, introducing an SSP into a neighborhood does not lead to increased crime.

-

The cost per HIV infection prevented through an SSP is estimated to be between $51,601 and $61,302. The estimated lifetime cost of treating an HIV positive person is $379,668. That means that for every $1 spent on preventing HIV by funding SSPs, $6.38-$7.58 is saved.

In 2013, the yearly cost of treating Hepatitis C in the United States was estimated to be $6.5 billion. Since injection drug use accounts for 68% of hepatitis C infections in the United States, this expense could be greatly reduced through SSPs.

The National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) of the National Academy of Sciences conducted an expert consensus report and systematic review in order to understand whether or not SSPs facilitate, promote, or enable drug use. The report found that syringe exchange programs:

- Do not increase the frequency of injection drug use

- Do not expand networks of drug users / expand substance use networks

- Do not facilitate local crime

- Do not cause an increase in crime within close proximity to SSP locations

- Do not lead to an increase in local drug crime

THE PROPOSED BILL: CHANGING THE LAW

What’s in the bill?

Iowa’s current drug paraphernalia law does not allow for needle distribution or possession.

The proposed bill will amend this law to allow authorized needle exchange programs to distribute needles and for participants to possess needles obtained from these programs. Each participant, volunteer, and staff member will be issued a unique identification number and participant card.

When law enforcement officers encounter an individual in possession of paraphernalia, it is the responsibility of the individual to demonstrate that the paraphernalia was obtained legally through an authorized SSP by producing their unique identification number and participant card. Under the proposed legislation, law enforcement officers will not be held liable for unknowingly charging SSP participants with paraphernalia possession, if the charge is issued in good faith.

To read the full proposed bill click here.

Who will administer the needle exchanges? Where will they be?

Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) will administer the syringe service programs through existing infrastructure for HIV and hepatitis C prevention and care programs. Currently nine programs receive IDPH grants through the Integrated Testing Services (ITS) program. These nine sites will be charged with implementing syringe exchange programs in their communities and the surrounding region, including neighboring counties, small towns, and rural communities.

Programs asked to implement syringe service programs may include:

- Linn County Public Health – Cedar Rapids

- Johnson County Public Health – Iowa City

- Black Hawk County Health Department – Waterloo

- Cerro Gordo County Health Department – Mason City

- Council Bluffs City Health Department – Council Bluffs

- Hillcrest Professional Health Clinic – Dubuque

- Project of Primary Health Care & Polk County Public Health Department – Des Moines

- Scott County Public Health Department – Davenport

- Siouxland Community Health Center – Sioux City

THE COSTS: FUNDING & IMPLEMENTING SSPs

No state funds are requested to support implementation and expansion of SSPs in Iowa. There is no fiscal note associated with the proposed legislation, as funds are available to support SSPs from federal agencies and private foundations (along with potential support from local governments). As such, no funding will be diverted from existing programs. That means no dollars will be taken from law enforcement or substance use prevention program budgets to fund SSPs.

Public funding for SSPs:

- Federal funds: In November 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved Iowa to receive federal funding for SSPs implementation and operations, should the state modify the existing drug paraphernalia code. Additional federal funding has been made available to states from several federal agencies, including SAMHSA (utilizing State Targeted Opioid Response grant funds), HRSA, CMS, USDA, CDC, and HHS. Federal funding available for allocation may range from several hundred thousand dollars to several million dollars, depending on the grant, agency, or geographic area of focus.

- Local funds: County or municipal dollars may be utilized to support SSPs. Large metro areas across the U.S. have utilized local funds to supplement state, federal, and private funding sources. Local government entities may elect to contribute funds to SSPs if they so wish.

Private funding for SSPs:

- A number of private foundations provide annual funding to SSPs around the United States. The Elton John AIDS Foundation is one such major private funder of SSPs in the U.S. and in 2017 provided almost $10 million dollars in grants to SSPs. Other private funders of SSPs include Gilead, AIDS United, the Comer Family Foundation, Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS, the Elizabeth Taylor Foundation, MAC AIDS Fund, the Arnold Foundation, the National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors, the Harm Reduction Coalition, the Drug Policy Alliance, AmFar, and many others.

Additional private funding and support may be obtained from Iowa-based community foundations and/or family foundations.

THE CONTEXT: SSPs AROUND THE U.S.

Year SSPs implemented: 1994

Legal status: Distribution and possession of paraphernalia was never prohibited via WI state code. Did not require policy change to implement programs.

SSP infrastructure: Operated by a private non-profit health care agency (14 sites across the state) and a county public health department in one community.

Key players: Vivent Health (Formerly AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin)

Year SSPs implemented: 1993

Legal status: Programs formally legalized in 2019. Legal exemption granted in 1995 for programs to operate legally (without change to state code) as research projects

SSP infrastructure: State health department does not coordinate. Few programs (2-3) exist outside of Chicago. Chicago / Cook County Dept. of Public Health is a major funder.

Key players: Chicago Recovery Alliance

Year SSPs implemented: 1996 or before

Legal status: Distribution and possession of paraphernalia was never prohibited via WI state code. Did not require policy change to implement programs.

SSP infrastructure: State health department does not coordinate or oversee programs – programs are independently run by nonprofits. Few programs exist outside of the Twin Cities.

Key players: Southside Harm Reduction

Year SSPs implemented: 2018

Legal status: Legalized in 2018, one program (Fargo) operated for several years in advance of law change.

SSP infrastructure: Programs primarily operated via county health departments.

Key players: n/a

Scott County, IN is a county like many of Iowa’s counties. In 2019 the county’s population was just under 24,000. HIV was previously exceptionally rare in Scott County. Between 2004 and 2013, there were 5 HIV infections reported in the county. SSPs were illegal in Indiana, and none operated in Scott County. But in late 2014 and early 2015, disturbing reports began to emerge of dozens of people testing positive for HIV. Between November 2014 and November 2015, there were 181 new cases of HIV. Almost 90% of these cases were linked to injection drug use. By the end of the outbreak, 235 cases were documented.

A 2019 study from Brown University found that if a syringe exchange program had been established prior to the outbreak, 90% of the HIV cases would have been prevented.

On March 25, 2015, former Indiana Governor Mike Pence declared a public health emergency in response to the outbreak and signed an executive order that temporarily authorized needle exchange program. The program was successful, with 277 enrollees and more than 90,000 syringes distributed and returned between April and October 2015 and the number of new HIV infections decreased. The Scott County outbreak was a wake-up call for advocates, epidemiologists, policymakers, and program administrators throughout the United States. Never before had the country seen such a swift outbreak of HIV in a rural community.

Soon after the outbreak ended, Congress overturned a long-standing ban on using federal funding to support syringe-exchange programs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) then released a report identifying the 220 rural counties in the United States that were most vulnerable to HIV and HCV outbreaks among people who inject drugs. The director of the CDC at the time, Tom Frieden, called the sharing of unsterile syringes a “horrifyingly efficient route for spreading HIV, hepatitis, and other infections” and called for states to implement more syringe-exchange programs.

Key players: Harm Reduction Ohio

Year SSPs implemented: 1990s (underground), mid-2000s (underground)

Legal status: Legalized via state legislature 2016

SSP infrastructure: State health department hosts application process to authorize organizations that wish to operate a program. ~25 authorized programs across the state, <10 with effective programming, few receive state funds.

Key players: North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition; Olive Branch; Urban Survivors Union; Western North Carolina AIDS Project; Twin City Needle Exchange; Steady Collective;

Year SSPs implemented: 2018

Legal status: Legalized via state legislature 2018

Key players: Idaho Harm Reduction Project

Year SSPs implemented: 1995 (Atlanta program implemented)

Legal status: Legalized statewide 2019 via legislative process

Key players: Atlanta Harm Reduction

Year SSPs implemented: 2016 (Miami only), 2018 (statewide)

Legal status: Legalized via state legislature for initial pilot program (municipal level), followed by entire state legalization (revision to drug paraphernalia code)

SSP infrastructure: Independent organizations may implement programs. 2 established to date, with 2 others planning for implementation

Key Players: IDEA Exchange, Rebel Recovery

Key Outcomes

-

- Hospital Costs of Injection Drug Use in Florida

- Interest in linkage to PrEP among people who inject drugs accessing syringe services; Miami, Florida

- Syringe disposal among people who inject drugs before and after the implementation of a syringe services program

- A comparison of syringe disposal practices among injection drug users in a city with versus a city without needle and syringe programs

- A Cost Analysis of Hospitalizations for Infections Related to Injection Drug Use at a County Safety-Net Hospital in Miami, Florida

- Baseline differences in characteristics and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs by syringe exchange program modality: an analysis of the Miami IDEA syringe exchange

- Rapid Identification and Investigation of an HIV Risk Network Among People Who Inject Drugs –Miami, FL, 2018

- The University of Miami Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) Syringe Services Program – A Blueprint for Student Advocacy, Education, and Innovation

- Examining risk behavior and syringe coverage among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program: A latent class analysis

- Student-Run Free Clinic at a Syringe Services Program, Miami, Florida, 2017–2019

- Baseline prevalence and correlates of HIV and HCV infection among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program; Miami, FL

- Hospital Costs of Injection Drug Use in Florida

Year SSPs implemented: 2016

Legal status: Legalized 2016, no programs operated prior to legalization

SSP infrastructure: Over 50 programs operate via county and local health departments. Lack of reach into rural communities. Often criticized for poor community engagement and lack of trust among people who use drugs.

Key players: Kentucky Harm Reduction Coalition

THE SUPPORTERS: IOWA LAW ENFORCEMENT ENDORSE SSPs

“SSPs save money, lives, and take used needles off the streets, which protects both law enforcement and the public. Now is the time to lift legal barriers to SSPs, get more in operation, and bring them out into the open through political support.”

Chief Michael Tupper

Marshalltown

Chief of Police, Marshalltown Police Department

“I fully support the implementation of Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) for injection drug users. Recognizing the increase in heroin related incidents and deaths, it is important that law enforcement develop partnerships with a variety of stakeholders to have a an effective response to its use. Many police chiefs understand that while heroin use is a legal problem, it is primarily a public health problem that should be handled with combined efforts with public health officials. The challenge is how to get those who need treatment into the appropriate programs.”

Chief Mark Prosser

Storm Lake

Storm Lake Police Department

“One of the first things I thought was, needle exchange, what the heck? As a law enforcement officer, its something that I initially had an adverse reaction to. But when I started doing some more reading and we started having conversations, my mind was changed by just looking at the data.”

“[Among Republican legislators] I think the support, you’d be shocked to know how much support there really is when we start talking behind the scenes. Like anything else we deal with in the legislature, you have the moral implications vs. the costs, and the cost savings. And those are the three tiers we look at when we have these discussions. When we drill down into the data that is out there, the data clearly shows that the majority of hepatitis and AIDS infections comes from dirty needles. This program has been shown to be effective in other parts of the United States to reduce diseases. Most persons, when you show them the data, its just a matter of having thoughtful conversations and breaking it down. There is a lot of merit to this reducing infectious diseases. The most convincing case I will make, is that the data clearly shows that a syringe exchange program does lower the hepatitis C and HIV transmission rates. If there is a concern about individuals using money for needles instead of textbooks, you’re going to save money for textbooks and education down the road because we are going to lower health care costs inside our prison system.”

Senator Dan Dawson

Council Bluffs

Iowa Senate District 8, Special Agent, Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation

“Recognizing the increase in heroin related incidents and deaths, it is important that law enforcement develop partnerships with a variety of stakeholders to have an effective response to its use. Many police chiefs understand that while heroin use is a legal problem, it is primarily a public health problem that should be handled by public health officials. The challenge is how to get those who need treatment into the appropriate programs. SSPs create a point of contact with people with substance use disorders so they can access detoxification and treatment programs with help from community health outreach workers.”

Chief Jody Matherly

Iowa City

Iowa City Police Department

“The opioid addiction crisis affects Iowans from all walks of life every day, and it’s creating another epidemic: sharing needles to inject the drug. As a result, Hepatitis C and HIV are on the rise in Iowa. To help stem the tide, advocates recommend syringe exchange programs that provide clean needles to those struggling with addition. The Iowa Department of Public Health and the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition promote these programs to limit the impact of the opioid crisis. SF 2294 would allow syringe services programs in Iowa, under the oversight of the Department of Public Health. Although some believe this proposal would enable addicts, similar programs in other states have successfully reduced outbreaks of Hepatitis C and HIV, and have helped many get the substance abuse treatment they need. Some estimates show needle exchange programs make it five times more likely an addict will seek treatment.”

Senator Kevin Kinney

Oxford

Iowa Senate District 39, Lieutenant (retired), Johnson County Sheriff’s Office

“As a retired police officer, I see the value of a needle exchange program. Statistics support that it does NOT increase drug use. Needle exchanges would increase police officer and community safety. Ready availability of clean needles and cleaner disposal of dirty ones would greatly decrease accidental exposure to needles by police and the public. Studies confirm needle exchanges reduce disease transmission and increase substance abuse treatment, both of which increase public safety.”

Representative Wes Breckenridge

Newton

Iowa House District #29, Lieutenant (retired), Newton Police Department

Letters of support from law enforcement

Law Enforcement & Syringe Exchange Programs: The North Carolina Experience.

TAKE ACTION: BECOME AN ADVOCATE FOR LEGAL SYRINGE ACCESS PROGRAMS

Send a note, make a call, write a letter, organize your community, or donate your time.See the list of action steps and get involved now.