Legislative Priorities

Syringe Service Programs (SSPs)

The story of substance use in America is still unfolding. However, breakthroughs in research and evaluation of innovative programs are giving us a clearer picture of the problem and how to address it. Yet, hundreds of years of changing narratives has made it tough for everyone to get on the same page. The myths surrounding syringe service programs (SSP) are a great example. Read on for more information on what this life saving, evidence-based strategy is all about. Together, we can change the narrative to this story in Iowa.

The Characters

Rachel: A meth user who has struggled with her addiction for many years.

Lauren: An employee at the SSP who wants to help people in her community who want to help themselves, especially persons struggling with substance use disorder.

The Ideal Story

Rachel learns that she can avoid contracting HIV or hepatitis C if she visits an SSP. She’s not quite ready to enter treatment for her active addition but she doesn’t want to get sicker either. She visits the local center and is greeted by Lauren, one of the employees. Lauren isn’t judgmental. She is kind, compassionate, and understanding of where Rachel’s is currently at in her drug use. She intends to build trust with Rachel by showing compassion without judgement. She wants Rachel to feel comfortable returning to the SSP for help. In the long-term, the program’s objective is to have Rachel return here to talk to Lauren or her colleagues about opportunities for improving her wellbeing, which may include substance use treatment options.

Just like so many before her, Rachel is taking the first steps to helping herself. To meet the SSPs objectives, Lauren will support her in each step she takes.

Rachel is surprised when Lauren provides her not only with sterile needles but a full kit, complete with everything she would need to prepare and inject the drugs she uses. She learns that it’s because hepatitis C is highly infectious. It’s easily transferred from person to person by coming into contact with blood, which can be found on not only a syringe, but a tourniquet, preparatory container (like a spoon or one-time use “cooker”), or a filter. Further, Lauren tells her that sometimes people can end up in the hospital with costly bacterial infections that affect the blood and heart – these are caused when bacteria from the skin enter the bloodstream (for example, when a syringe is re-used), so Lauren provides Rachel with a package of alcohol wipes and reminds her never to re-use her own syringes. Lauren also provides her with a naloxone kit in case she or someone she uses with overdoses. Finally, Rachel also learned more about how to avoid STD’s and is provided other information about how to stay as healthy as possible. She’s learning what her body is experiencing each time she uses drugs.

At the end of the day, Rachel feels more informed about her health and wellbeing. She now has a trusted source of information to turn to when she has questions. She also left trusting that Lauren will not judge her when she returns with used needles to exchange for more sterile ones. This was a good experience. Before leaving, Lauren gives Rachel a small biohazard container and lets her know that she can bring back her used syringes to the SSP once the container is full. She won’t need to worry about being arrested for paraphernalia because as long as she is a registered participant in the SSP program (carrying an identification card Lauren will provide her with), she will be permitted to return and dispose of her used syringes safely.

Changing the Narrative

This scene is surprising to most people. The story of addiction in America has told us that we are not to “enable” Rachel’s drug use. We should turn our backs on her because she lacks will power and is selfish. We are told to teach our loved ones “tough lessons” to show them the consequences of their poor choices. Right?

But, it’s a different story for persons who suffer from heart disease, diabetes or tobacco-induced cancers, nor should we. Instead, we surround them with a compassionate care team who will educate them about their risks, help them navigate their service options, and support them with follow-up services. Why shouldn’t we do the same for this disease? They deserve compassionate care, too. Why are we not taught to meet them where they’re at to help them change their behavior and support them through another chance at a healthier life?

How SSPs work and why they're effective

There’s a story in public health lore:

A group of people were fishing on the river bank when they saw a woman struggling in the current. They rescued her. Soon, they saw a man struggling. They rescued him, too. This continued all afternoon.

Finally, a few members of the group looked upstream to find out why so many people were falling in. They noticed the river’s edge did not have any warning signs or protective barriers. The group went to community leaders to report the number of victims they had rescued and explain the reasons they were falling in.

Community leaders agreed to install a protective guard and post warning signs. Preventing the problem saves valuable resources, energy, and lives.

SSPs are part of the downstream strategy for addressing substance use disorders in our state. They focus on the individual and they meet them where they’re at in their story of dependence. We at the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition believe they are worthy of the resources and energy it takes to help them. It’s not wasted effort, though, SSPs are effective.

Demonstrated effectiveness in achieving objectives

(Note: These are just a few studies in a rich trove of research. Also known as syringe exchange programs or needle exchange programs, SSPs have been studied in the United States for over 30 years and implemented in urban, suburban, and rural communities.)

- Objective 1: Facilitate access to and uptake of services and interventions for reducing overdoses.

A recent study found that individuals who use drugs who were recently incarcerated are at significantly higher risk of overdose and are more willing than their non-incarcerated peers to receive training for and administer naloxone when this is offered by a syringe services program, making syringe service programs a particularly important intervention for assisting these high-risk individuals. (1) - Objective 2: Lower the frequency of syringe sharing and re-use to reduce the rates of infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C and to reduce needle-stick injuries to law enforcement and first responders.

– A study in San Francisco found that more than 65% of interviewees who used drugs regularly disposed of syringes at syringe service programs, and almost none disposed of syringes at pharmacies, a method that some states have tried.(2,3)

– SSPs across the US have been shown to decrease the number of new HCV and HIV cases by up to 80%.

– Law enforcement officers experience a 33% risk of being stuck by a needle during their career. SSPs are shown to reduce needle stick injuries to law enforcement officers by 66%.(4,5) - Objective 3: When participants are ready, help them navigate toward treatment for their substance use disorder.

Participants are five times more likely to enter drug treatment and 3.5 times more like to stop injecting compared to non-participants.(6)

This isn’t a new idea

The majority of states have changed their narrative and thus, the fates of many.

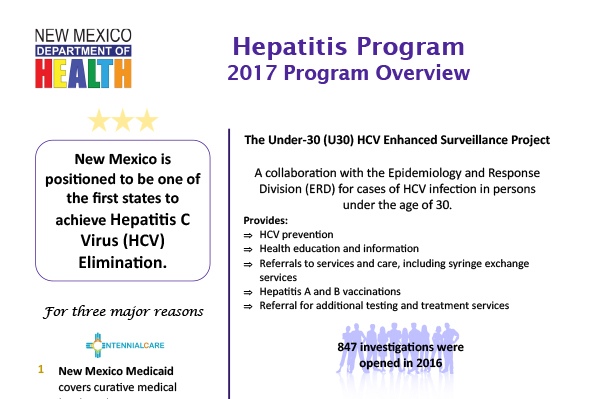

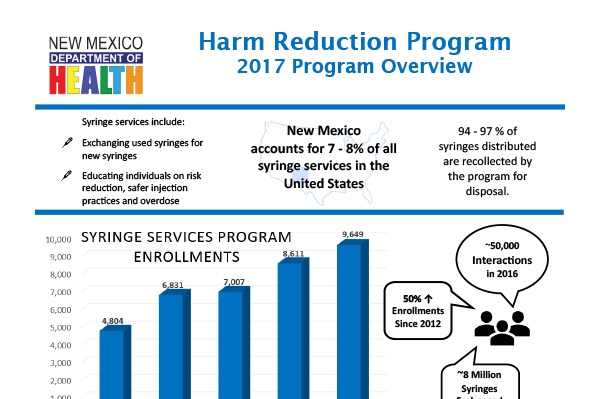

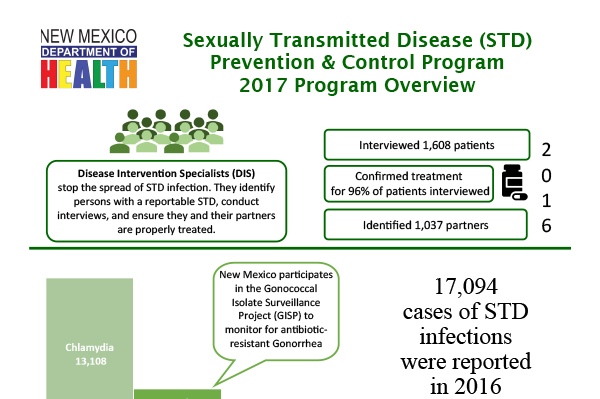

New Mexico’s department of public health administers the state’s syringe service program. There are 40 syringe exchange programs in the state, and most are operated within local public health departments. 9 are operated by community-based organizations. Syringe exchange became legal in 1997, and now the program has 40,000 participants per year and exchanges 4 million needles per year. The syringe service programs offer naloxone and overdose prevention services, provide testing for HIV and hepatitis, offer counselling and support groups, and provide suboxone treatment.

Syringe exchange programs are often believed to encourage and promote drug use. However, in a study of syringe exchange participants in New York, new participants decreased their injection frequency by eight percent after enrolling in a syringe exchange program (14).

Syringe exchange programs began to operate in New York in 1988. In 1990, 54% of injecting drug users were HIV positive, and 90% had hepatitis C. By 2012, 3% were HIV positive, and 63% had hepatitis C, illustrating the power of syringe exchange programs to significantly reduce infectious disease prevalence in a population. During this period, the syringe exchange programs grew from exchanging 250,000 syringes annually to exchanging over 3 million annually (14).

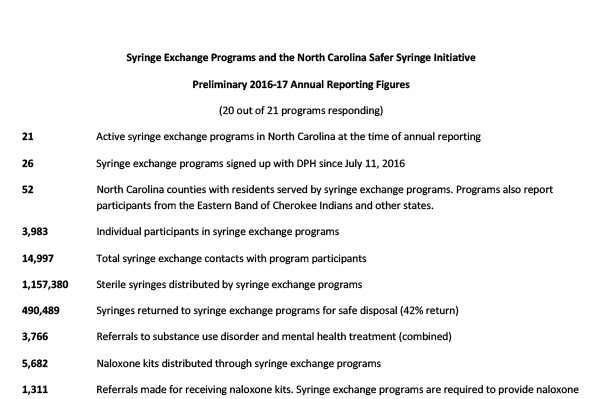

North Carolina legalized syringe exchange programs in 2015. Since then, the state has developed 21 programs that serve 52 counties. Since legalization, 3,983 individuals have participated in syringe exchange programs, resulting in a total of 14,997 contacts with program participants and 1,157,380 sterile syringes distributed.

Syringe exchange programs serve as excellent opportunities to distribute naloxone, and to make connections to treatment programs – NC has made 3,766 referrals to substance use disorder treatment and distributed 5,682 naloxone kits. Program participants have reported 2,187 overdose reversals.

These programs have administered 738 hepatitis C tests, identified 138 positive hepatitis C results, and administered 2,647 HIV tests, with 6 positive results.

Utah legalized syringe exchange programs in May 2016. The law required the Utah Department of Health to enroll agencies to run syringe exchange programs, collect data, and make reports to the state legislature on the programs. The syringe exchange programs are required to provide new syringes, offer syringe disposal, and make referrals or offer services for HIV/HCV testing, substance use disorder treatment, and naloxone and overdose prevention. The law did not provide funding for the programs. Since the launch of the programs in December 2016, Utah has distributed over 180,000 syringes, collected almost 70,000 used syringes, and worked with over 5,000 participants. The program is new, and program evaluation takes time and money – it will take several years to learn how the program impacts rates of infectious disease and how successfully programs connect Utah residents into services (3).

Since 1995, the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin state department of public health have operated 10 syringe exchange programs throughout the state. In 1995, there were 235 new HIV infections among people who inject drugs. However, in 2015, there were two new HIV infections in this community (1).

In 2015, of 47,680 syringe exchange participants, 8,046 referrals to drug treatment were made (1).

Syringe exchange programs often make referrals to treatment. A study of one syringe exchange program found that over the course of one week, 40% of participants entered treatment when offered services by a case manager or social worker. Among these participants, the case manager arranged payment, transportation, and enrollment in a treatment program. Among participants who were handed a paper referral but did not receive assistance from a case manager, 26% entered a treatment program within the week (2). Both case management services and referrals from syringe exchange programs are useful pathways to link people into treatment services.

A 2000 study of syringe exchange participants in Seattle found that people who participated in a syringe exchange were 2.5 times more likely to reduce their injection frequency than people who had never participated in a syringe exchange program. They were 3.5 times more likely to stop injecting drugs all together (compared to those who had never participated in a syringe exchange program). New users of syringe exchange programs were five times more likely to enter drug treatment programs than those who did not use the programs (13).

Washington state legalized syringe exchange in 1992. Their state health department coordinates the work of many different programs spread around the state. In 2016 87,806 individuals were served, the majority through mobile syringe exchange programs, non-traditional community locations, deliveries, outreach, clinics, and community-based organizations.

In 2016, 16,719,311 sterile syringes were distributed. 5,294 people were referred to drug treatment were made, as were 8,376 health care referrals, and 11,401 people participated in syringe exchange.

Syringe exchange programs are also an excellent opportunity to distribute naloxone and are an extremely effective pathway to prevent overdose deaths. In WA, 2,728 naloxone kits were distributed in the first eight months of 2017. 1,814 people received kits, including 349 law enforcement officers and 1,465 people who use drugs. In just eight months, 392 overdose reversals were reported. 100% of reversals were performed by drug users.

Syringe service programs are often the first encounter that people who inject drugs have with health and social services. These programs provide a resource for PWID to seek out additional services, and the referrals to treatment services made by SSPs often come at the request of program participants. In the first seven months of operation of the New Haven syringe exchange program, 25% of participants requested drug treatment referrals. 60% of those individuals subsequently entered a detoxification program (10). Of the 40% who did not enter treatment, lack of health insurance was cited as the reason.

Florida has one legal syringe exchange that serves Miami-Dade county (legalized in 2015), and has seen how costly it can be to have no syringe exchange program. In a study of people who inject drugs (PWID) before syringe exchange programs were implemented, over the course of one year 349 PWID were admitted to a county safety net hospital with bacterial infections from drug injection (preventable by use of sterile syringes). These hospitalizations resulted in $11.4 million in healthcare expenses and 17 deaths. The vast majority of hospitalized PWID (92%) were either uninsured or relied on publicly funded insurers such as county, state and federal programs. While it is customary for hospitals to bill in excess of expected payment for services rendered based on pre-negotiated reimbursement rates, Florida Medicaid was billed $18.4 million over the study period for injection drug use-related infections (4).

Hawai’i established syringe exchange programs in 1989, and became the first state to fully fund and coordinate syringe exchange programs through its department of public health. Hawai’i’s success and efficacy can be seen through its reduction of the transmission of HIV. In the U.S., one third of all HIV infection cases are due to injection drug use. In Hawai’i this proportion is only 13%. Further, among syringe exchange participants in Hawai’i, there is an HIV prevalence of 0% (12).

Indiana has no comprehensive, statewide syringe exchange program, and until 2015 did not have legal syringe exchange. In Scott County, IN, a rural community in the southern portion of the state, there were five cases of HIV diagnosed from 2004 – 2014. During this time, opioid use and injection drug use began to increase in Scott county. Then, from November 2014 – August 2015, 181 residents tested positive for HIV. After declaring a state of emergency in March 2015, Governor Mike Pence issued an executive order legalizing syringe exchange. The program began operation in August 2015. Between September and October 2015, not a single person tested positive. Indiana will continue to incur costs from this outbreak for decades: the lifetime treatment cost for one person with HIV infection is $378,668. Other states, like New York, Wisconsin, and Hawai’i have effectively eliminated HIV through their syringe exchange programs and avoided such human and financial costs (5).

No study has ever found that syringe exchange programs increase drug use or rates of crime. A Maryland study examined crime rates and arrest data in a neighborhood during the six months before and after the opening of a syringe exchange program. The study found that when controlling for all variables, the number of arrests decreased in the period following the opening of the syringe exchange (8).

Syringe exchange programs have a long history of facilitating entry into treatment programs for substance use disorders. A 2006 study of 1,490 people who injected drugs in a Maryland community explored whether or not people sought out treatment services through their syringe exchange programs. Between 1994 and 1998 when the first syringe exchange opened in the community, 25% of the program participants entered detoxification. The study found that needle exchange program participants were 3.2 times more likely to enter detoxification than people in the community who used drugs but did not participate in the needle exchange program (9).

For those persons who do not participate in a syringe exchange program, the process of entering treatment can be daunting – long wait times, lack of transportation, and insurance paperwork can make navigating the treatment system extremely difficult to an individual. Although syringe exchange is not legal in Missouri, a syringe exchange program still operates. In this program, employees keep files on each syringe exchange program participant. During each visit to the syringe exchange, employees discuss readiness to enter treatment and make notes of participants’ readiness. Once the individual is ready to enter a treatment program, the employee navigates and arranges entrance into the treatment program. Because syringe exchange programs have relationships with drug treatment programs, this linkage to care is easily navigated (11).

In 2006, New Jersey legalized a syringe exchange pilot program. Through 2011, the syringe access program enrolled 9,912 participants. 22% of those participants (2,160) were admitted to methadone or suboxone treatment programs. Just under 2 million syringes were distributed, and the state elected to continue the program (6).

The need is urgent

In December 2017, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) sent a letter to Governor Kim Reynolds notifying her that Iowa is at high risk for a HIV outbreak among people who inject drugs. Similar to the now infamous HIV outbreak of 2015 that took place in rural Scott County, Indiana, a HIV outbreak could impact the health of thousands of Iowans and lead to a lifetime cost of over $750,000 in taxpayer dollars for treatment of each person infected. There is an urgent need for Iowa’s legislature to act and change the law that permits SSPs from opening, in order to prevent a public health catastrophe. It’s time to make sure that we save taxpayer dollars.

Law Enforcement Officers Support Syringe Service Programs and Needle Exchange

“SSPs save money, lives, and take used needles off the streets, which protects both law enforcement and the public. Now is the time to lift legal barriers to SSPs, get more in operation, and bring them out into the open through political support.”

Chief Michael Tupper

Marshalltown

Chief of Police, Marshalltown Police Department

“I fully support the implementation of Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) for injection drug users. Recognizing the increase in heroin related incidents and deaths, it is important that law enforcement develop partnerships with a variety of stakeholders to have a an effective response to its use. Many police chiefs understand that while heroin use is a legal problem, it is primarily a public health problem that should be handled with combined efforts with public health officials. The challenge is how to get those who need treatment into the appropriate programs.”

Chief Mark Prosser

Storm Lake

Storm Lake Police Department

“One of the first things I thought was, needle exchange, what the heck? As a law enforcement officer, its something that I initially had an adverse reaction to. But when I started doing some more reading and we started having conversations, my mind was changed by just looking at the data.”

“[Among Republican legislators] I think the support, you’d be shocked to know how much support there really is when we start talking behind the scenes. Like anything else we deal with in the legislature, you have the moral implications vs. the costs, and the cost savings. And those are the three tiers we look at when we have these discussions. When we drill down into the data that is out there, the data clearly shows that the majority of hepatitis and AIDS infections comes from dirty needles. This program has been shown to be effective in other parts of the United States to reduce diseases. Most persons, when you show them the data, its just a matter of having thoughtful conversations and breaking it down. There is a lot of merit to this reducing infectious diseases. The most convincing case I will make, is that the data clearly shows that a syringe exchange program does lower the hepatitis C and HIV transmission rates. If there is a concern about individuals using money for needles instead of textbooks, you’re going to save money for textbooks and education down the road because we are going to lower health care costs inside our prison system.”

Senator Dan Dawson

Council Bluffs

Iowa Senate District 8, Special Agent, Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation

“Recognizing the increase in heroin related incidents and deaths, it is important that law enforcement develop partnerships with a variety of stakeholders to have an effective response to its use. Many police chiefs understand that while heroin use is a legal problem, it is primarily a public health problem that should be handled by public health officials. The challenge is how to get those who need treatment into the appropriate programs. SSPs create a point of contact with people with substance use disorders so they can access detoxification and treatment programs with help from community health outreach workers.”

Chief Jody Matherly

Iowa City

Iowa City Police Department

“The opioid addiction crisis affects Iowans from all walks of life every day, and it’s creating another epidemic: sharing needles to inject the drug. As a result, Hepatitis C and HIV are on the rise in Iowa. To help stem the tide, advocates recommend syringe exchange programs that provide clean needles to those struggling with addition. The Iowa Department of Public Health and the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition promote these programs to limit the impact of the opioid crisis. SF 2294 would allow syringe services programs in Iowa, under the oversight of the Department of Public Health. Although some believe this proposal would enable addicts, similar programs in other states have successfully reduced outbreaks of Hepatitis C and HIV, and have helped many get the substance abuse treatment they need. Some estimates show needle exchange programs make it five times more likely an addict will seek treatment.”

Senator Kevin Kinney

Oxford

Iowa Senate District 39, Lieutenant (retired), Johnson County Sheriff’s Office

“As a retired police officer, I see the value of a needle exchange program. Statistics support that it does NOT increase drug use. Needle exchanges would increase police officer and community safety. Ready availability of clean needles and cleaner disposal of dirty ones would greatly decrease accidental exposure to needles by police and the public. Studies confirm needle exchanges reduce disease transmission and increase substance abuse treatment, both of which increase public safety.”

Representative Wes Breckenridge

Newton

Iowa House District #29, Lieutenant (retired), Newton Police Department

Letters of support from law enforcement

Law Enforcement & Syringe Exchange Programs: The North Carolina Experience.

2020 Syringe Service Bill Draft

Citations

1. Barocas JA, Baker L, Hull SJ, Stokes S, Westergaard RP. High uptake of naloxone-based overdose prevention training among previously incarcerated syringe-exchange program participants. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:283-286. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.023

2. Bluthenthal RN, Ridgeway G, Schell T, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Kral AH. Examination of the association between syringe exchange program (SEP) dispensation policy and SEP client-level syringe coverage among injection drug users. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2007;102(4):638-646. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01741.x

3. Kerr T, Small W, Buchner C, et al. Syringe Sharing and HIV Incidence Among Injection Drug Users and Increased Access to Sterile Syringes. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1449-1453. doi:10.2105/ AJPH.2009.178467

4. Lorentz J, Hill J, Samini B. Occupational needle stick injuries in a metropolitan police force. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:146–150.

5. Groseclose SL, Weinstein B, Jones TS, Valleroy LA, Fehrs LJ, Kassler WJ. Impact of increased legal access to needles and syringes on practices of injecting-drug users and police officers—Connecticut, 1992-1993. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 1995;10(1):82–89.

6. Hagan H, McGough JP, Thiede H, Hopkins S, Duchin J, Alexander ER. Reduced injection frequency and increased entry and retention in drug treatment associated with needle-exchange participation in Seattle drug injectors. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19(3):247-252.

Additional resources on the effectiveness of SSPs.