Black lives matter.

An opinion. A radical political ideology. An example of “reverse racism.” The name of a terrorist organization. For far too many people, these three simple words are capable of invoking responses ranging from indifference to outright hostility. And yet, from the beginning, the words Black Lives Matter have meant simply this: the lives of Black people have value and meaning.

From the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota, Tony McDade in Florida, Breonna Taylor in Louisville and Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, recent events have spurred protest and catalyzed a national conversation about anti-Black racism. While these four deaths are some of the most recent and the most public, they are certainly not the only killings which Black communities are grieving and responding to in this moment. After reading a letter written by the President of Emerson College, I wondered if the 8 minutes that it took for a police officer to kill George Floyd just exceed the number of minutes that make up a person’s “lifetime bandwidth” to witness and experience dehumanization, brutalization, and injustice perpetrated by white people. 8 minutes is just enough time to review a mental film reel of lynchings, murders, and Black death: Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Emmett Till. Sandra Bland. Freddie Gray. Tamir Rice. Eric Garner. Whatever “storage space” that must exist within a collective group of human beings to hold trauma and grief appears to, finally, be full. The anguish reflected in the events of past weeks suggests that for Black Americans, enough is enough. No capacity remains to process another loss of Black life. These aforementioned events also remind us of the lengths that white people will go to in order to protect the social order in which we experience dominance. It is abundantly clear that we have chosen to prioritize our own comfort, protection, and ease over a fundamental respect for Black life.

The violence perpetrated by law enforcement officers in past weeks is alarming. The arrests of journalists along with the brutal assaults on crowds peacefully demonstrating or individuals simply going about their daily lives, is an expression of the polices’ desire to maintain dominance and white supremacy. But it is not necessarily a new phenomenon. Policing is an institution with its roots in anti-Black racism. It is well known that America’s initial police forces were slave catchers, and these militias evolved into a profession that serves as the protectorate for the wealth and property of white people. While today the police are charged with protecting the safety of all individuals in a community, it is reasonable that an institution with its roots in such a history may not necessarily be one without bias, or that is capable of fulfilling this charge.

The statements in the paragraph above have long been viewed as “too dangerous” or “too fringe” for organizations to endorse, especially in Iowa. But a willingness to speak truthfully about the vestiges of slavery, and their impacts today, is reflected in recent statements from the nation’s leading health care and public health organizations: In a statement released last week by the American Medical Association (AMA), titled, “Police brutality must stop,” the most influential entity representing physicians in the U.S. recognized that while many who serve in law enforcement are committed to justice, police violence is a striking reflection of the American legacy of racism. The AMA outlined a growing body of medical research that documents the significant race-based disparity in experiences with police violence and noted that such experiences are linked to adverse chronic health outcomes for all Black people. Police violence results in higher levels of chronic stress among Black Americans, which manifests in worse mental health outcomes and is embodied through shorter life expectancies. This tells us that policing is simply not an institution that can create or ensure safety for Black communities.

At the same time, it is necessary that I recognize the humility and thoughtful leadership that are demonstrated in statements from Iowa’s law enforcement community on the killing of George Floyd. In particular, statements from the Iowa Police Chiefs Association and from Sgt. Brad Kunkel (the winner of yesterday’s Democratic primary election for Sheriff in Johnson County) model a preference for de-escalation and a willingness to engage in dialogue, even when it is uncomfortable. There are highly varied relationships between community members and their law enforcement institutions across the state. The vast majority of individuals who work in Iowa’s law enforcement professions do so because of a commitment to the belief that our world can be transformed into one that establishes safety for all. While we may at times disagree on the specific tactics or policies that are necessary or effective, I believe that all of our work can ultimately be united in the desire to create communities where everyone can experience peace, freedom, and joy. For this reason, IHRC is committed to building relationships with all community members and leaders, including individuals employed by law enforcement agencies, across our state. Since 2016, we have maintained a desire and willingness to engage in conversations with law enforcement that allow everyone to be fully seen.

As communities examine the role of racism in the justice system and beyond, the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition is responding to these events and the resultant calls to action from Black leaders. We, in turn, call on our elected leaders to publicly and deliberately engage with the requests for structural change, divestment in law enforcement institutions, and investment in safety, wellbeing, and healing for Black communities.

The purpose of this statement and call to action is three-fold:

First

To offer the briefest of responses to those Black folks who we live and work alongside and who are our colleagues, clients, patients, acquaintances, dear friends, service providers, neighbors, strangers, mentors, writers, friends’ babies, elected officials, celebrities, teachers, lovers, healers, sisters, brothers, children: you are heard. Both in your expressions of anguish and insistence that real, lasting, structural change happen, and that it happens not in a month or in a year, but now.

Second

To offer a statement that is primarily directed towards white people (particularly and especially those living in Iowa) that articulates Harm Reduction’s ideological relationship with racial justice and anti-racism work; highlights, in Floyd’s killing, the invocation of a process of dehumanization that is deeply intertwined in policies that criminalize drugs; and invites engagement, partnership, and accountability in IHRC’s work.

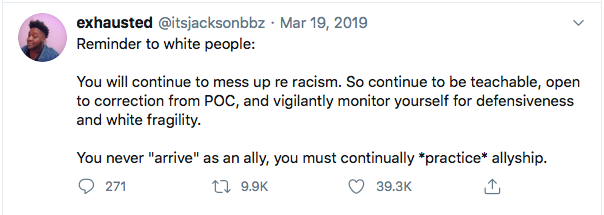

As a young organization, we are committed to receiving and responding to feedback as it concerns the themes discussed above and in the coda that follows. Perhaps most importantly, we understand that as an organization that is founded and led by white people, just as much of the work to be done concerns our own processes, strategies, and operations, which we will continue to share information about publicly. We affirm the idea that anti-racism is not a destination, and that as white people we will never become un-racist. A few days or weeks of training and reading may facilitate personal growth, but does not undo a culture that has been built over the course of many centuries. As such, we are engaged in a constant process of conversation, learning, and growth, and I fully expect that our attempts at ally-ship will at times be imperfect and at others potentially ill-informed. It is for this reason that I welcome the opportunity to receive feedback, and invite you to share your thoughts. And whether that be in a week or in two years, the prioritization of accountability is sincere

Third

To urge local leadership to consider the aforementioned statements from the American Medical Association, the Drug Policy Alliance, the American Public Health Association, and the specific calls to action from those leaders who affirm that Black Lives do Matter and entertain this question: Can our community guarantee: not one more loss of Black life at the hands of police? In responding to this question, it is critical that elected leaders steer away from the allure of reforming the current system through tactics that are well known to be ineffective, like implicit bias trainings, early warning systems for poor conduct, or civilian review boards. While none of these tools are inherently evil, the current moment makes clear that an institution cannot be reformed if it was never meant to protect Black lives in the first place.

During the month of June, IHRC will be sharing a number of updates, events, and projects that connect to the topics and themes in this statement. While the majority are previously planned and part of our ongoing work that relates to criminal justice reform, drug policy advocacy, and the provision of drug user health services across a number of Iowa communities, several initiatives are planned as part of our internal and external response to the events that have occured in the past week.

To echo the sentiments conveyed above, I invite you to contact me at sarah@iowaharmreductioncoalition.org at any time. Please feel free to reach out with your questions, thoughts, or concerns.

Sincerely,

Sarah Ziegenhorn

Founding Executive Director

Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition

Coda: A Deeper Dive

At the Intersection: Harm Reduction & Racial Justice

In the events leading up to the killing of George Floyd and in the public conversation held in the aftermath of his death, drug use has played an often subtle but critical role. This comes as no surprise, given the way in which drug use is meant to establish deviance and indicate poor moral character. As Floyd was held to the ground by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, another police officer looks on and states to a crowd of youth who were gathered nearby, watching and filming the encounter, “This is why you don’t do drugs, kids.” Earlier in the encounter, another officer and Chauvin discuss “excited delirium,”a term that is not recognized in medicine and has been historically used in law enforcement settings to describe alterations in consciousness and mental status attributable to poly-drug use, as well as establish a cause for sudden death while in police custody. The term is controversial and many in medicine believe that it is used as biological justification for deaths among Black men that result from police violence. In the criminal complaint associated with his death, a press release summarizing a forensic report asserts the idea that his death may not have been the result of police force, but rather by drug use: “The combined effects of Mr. Floyd being restrained by the police, his underlying health conditions and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death.” In the results from an autopsy ordered by Floyd’s family, released today, Floyd’s cause of death is listed as asphyxiation due to compression of nerves in his back and neck. In all of these moments, we are led to believe that George Floyd’s death is a reasonable or expected outcome for someone who may possess or use drugs. Kassandra Frederique, the incoming Executive Director of the Drug Policy Alliance summarizes the meaning of these references to drug use:

“With George Floyd most recently, Breonna Taylor earlier this month, and countless others before them, perceived drug possession and drug use served as a justification by law enforcement to dehumanize, strip dignity from, and ultimately kill people of color.”

In a statement from the Drug Policy Alliance, released late last week, Kassandra Frederique states why the work to reform drug policy is fundamentally linked with the work for racial justice:

“Drug involvement–whether perceived or real–has provided a convenient excuse for these violent and too often fatal law enforcement interactions. [We must] continue fighting to remove drug involvement as a cover for disregarding the dignity and sanctity of human life. And we will challenge and hold these institutions accountable. We refuse to stand by while another person cries out, as Eric Garner and George Floyd did, “I can’t breathe,” as law enforcement ends their life.

Ending the failed war on drugs will not legalize Black people, but it will disrupt a system that chips away daily at the very core of our humanity. We don’t need symbolic gestures, we need to strategize, organize, and build campaigns to ensure this doesn’t happen again. We stand ready to work with our allies to do our part.”

The War on Drugs & George Floyd Collide

Harm Reduction is an ideological approach to drug use that views the expertise gained through lived experience as paramount. Harm Reduction prioritizes the voices, knowledge, and wisdom of people with lived experience and understands that in order to create communities that are healthy, safe, and whole, the people who are directly impacted must be centered and intimately involved in decision making, policy development, and program implementation. With regards to substance use, we understand that people who use drugs (PWUD) expect to be engaged in the creation of any policy or program that is meant to serve or improve the lives of PWUD. Thus, we recognize the fundamental importance of centering the voices and expertise of Black people in decision-making (of any kind and at all levels) that concerns the conditions in which Black Americans live, including but not limited to racism and the legacy of slavery as an institution.

Harm Reduction is also a social movement and community of people working for justice, dignity, freedom, and respect for the people who use illicit, psychoactive drugs. We know that the lives of PWUD are deeply impacted by the laws under which these drugs are regulated, and that the origins of these regulations are deeply intertwined with late 19th century / early 20th century ideologies regarding race and power. Simply put, many of the race-based disparities that exist today in overdose deaths, HIV rates, arrests, sentencing lengths, and recidivism rates are the outcome of a legal framework that has assigned meaning to classes of drugs by connecting their use with racial and ethnic identity as a means of establishing and perpetuating deviance. The state has carefully cultivated the propaganda that drug use begets deviance, violence, and disorder thus begets a system in which those people who use drugs must be regulated, policed, and controlled in order to reduce violence, deviance, and disorder for the broader collective to be guaranteed safety.

Here is a fundamentally important point: While there are obvious parallels between the struggles and institutional hostility faced by PWUD and BIPOC, we are in no way claiming equivalency between the two, only highlighting that the similarities provide motivation and strengthen our desire to work to dismantle the legacy of white supremacy and entrenched racism.

Harm Reductionists recognize that our day to day work is often technical and focused on minimizing risks for adverse health outcomes at multiple scales, from training individuals to administer a medication that may save their life in the event of overdose, to debating the minutiae of the language in a bill that proposes minor revisions to the Iowa code. Yet we also know that this work is also deeply symbolic. Our sustained commitment is reflective of the belief in a much larger vision for what our communities could one day look like. This work is thus done in service to the idea that a world is possible where institutions and individuals engage with one another through relationships of support, healing, joy, and care, rather than punishment, authority, shame, or violence. In other words, it is to say that we fundamentally connect our work to racial justice, and know that to transform the way our world engages with drugs and the people who use them also means to transform the way we engage with Black lives and value assigned to them.