Abolish WHAT? A Primer and Resource Guide on Police & Prison Abolition

Disclaimer: This blog post is a resource developed in the spirit of education, conversation, and information sharing. At the time of publication, the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition has not released a position statement regarding specific policy proposals discussed in this blog.

Over the course of the last few days of May and the first week of June, our communities were forever transformed. Rocked by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Jamel Floyd, Ahmed Arbury, and so many more Black lives lost to police brutality, violence, and murder, Black community leaders have organized large-scale direct actions and engaged hundreds of thousands (perhaps millions) of Americans in non-violent protest.

These actions have spurred a national conversation about the fundamental nature of law enforcement. An institution with well known and well documented beginnings as the slave patrol, many Americans are asking the fundamental question: can this institution ever be expected to establish safety for all, when it was never meant to protect Black lives in the first place?

What to do with the police now? Breaking down the dominant narratives in public discourse

The discussion about the nature of police and the institution’s fundamental utility seems to be divided into three factions, each dominated by its own school of thought: In the first, police are viewed to be an essential part of any community, and without police forces, cities would see a substantial rise in violent crime and property crime. This camp views the status quo as largely positive, with the exception of a few bad apples who have severely damaged community-law enforcement trust. They recommend additional training for officers, including education on implicit bias and appropriate use of force, and some members of this camp have voiced support for increased accountability that will help to take the bad apples out of the system before they become the next Derek Chauvin.

The second camp seems to acknowledge that the status quo is not great, and that it’s time to make some changes. This faction sees a role for police in our communities – when presented with abolitionist ideas, individuals whose ideology most aligns with this group may ask, “What will people do if someone breaks into their house with a gun? Who are they supposed to call?” or “What about sexual assault? Won’t that go up if there are no police to deter rapists?” At the same time, team number two does express horror at the murder of George Floyd and the frequency with which Black lives are lost through similar police-involved killings. This group has coalesced around the need to reform the police, and the tactics encompassed by reform are featured in a highly publicized campaign called #8cantwait. Released within several days of Floyd’s murder, #8cantwait has been propped up by the media personality Deray, and local and state-level elected officials are reportedly inundated with requests from their constituents to implement the 8 tactics that make up this particular campaign. Included in this approach are these strategies: ban chokeholds and strangleholds; use of force policies; ban shooting at moving vehicles; require use of force continuum; require comprehensive reporting; require de-escalation; require warning before shooting; exhaust all alternatives before shooting. Some have remarked that they are horrified these strategies are not standard practice across law enforcement agencies.

Individuals from camp three, the abolitionists, have been highly critical of #8cantwait and of Deray. This campaign has been criticized as being, “dangerous and irresponsible for offering a slate of reforms that have already been tried and failed, that mislead a public newly invigorated to the possibilities of police and prison abolition, and that do not reflect the needs of criminalized communities.” Deray and Campaign Zero have also been accused of co-opting the language of abolitionists, and the campaign has applied the term Harm Reduction to a number of its strategies, creating a point of concern for individuals across the country whose work is entrenched an understanding of Harm Reduction as something much, much more transformative than political pragmatism and change that is incremental or merely symbolic. In reviewing the Campaign Zero website, a new graphic has debuted that heavily relies on harm reduction and abolition, but provides little context about these concepts and attributes no new tactics to these philosophies.

Read: #8cantwait

What a time to be alive

The abolitionists make up the final thought faction, and their interpretation of the solutions needed in this moment can perhaps be summarized as a counterpoint or response to the second group: The 8cantwait campaign promises to reduce police killings by 72%. At what point will we say that enough is enough? At what point will another loss of Black life be completely unacceptable? So unacceptable that in order to keep our commitment to protecting life, we are willing to invest in changes that are bold and disruptive. The abolitionists recognize that the terminology used to describe their theoretical approach is full of drama and can lead to confusion and fear, but when simplified, is not a unique phenomenon: if the current system of policing does not work, the funding that supports this system may be better allocated elsewhere. Public dollars invested in building support and providing care for Black communities can help to improve health, wellbeing, connectivity, and economic security. A byproduct of such an investment is a drop in crime. In the meantime, many community needs that are handled by police departments can be re-assigned and shifted elsewhere, particularly to community-based institutions that do not have a history that is as intimately tied to slavery and racism. The operative idea here is that policing is not working. In his seminal book, The End of Policing, scholar Alex Vitale writes,

“The problem is not police training, police diversity, or police methods. The problem is the dramatic and unprecedented expansion and intensity of policing in the last forty years, a fundamental shift in the role of police in society. The problem is policing itself.”

In this case, we are left with no other choice but to look to other institutions and professionals to fulfill the needs of the community. In response to the #8cantwait campaign, a group of thought leaders from this camp created an alternative campaign, #8toabolition. The strategies named in this campaign can be read in their entirety on the campaign’s website.

Read: #8toabolition

Understanding Abolition’s Goals: Resources for Learning

In the past two weeks, the overton window has been shifted to an extent that no one would have probably believed to be possible. And as many Americans encounter ideas about police reform and abolition for the first time, it is crucial to remember that these are not new ideas. Abolitionist thought has origins in the scholarship of Black feminist theorists, and leaders of this movement have invested many decades into the belief that a better world is possible.

I am writing about the divisions in the public discourse on policing not because it represents a particular area of expertise for me, but because this is fundamentally a conversation about the concepts of freedom, autonomy, care, support, and justice. It is a conversation about what it means to live in relationship with other human beings – and what commitments we are willing to make to one another. These concepts also lie at the heart of public discourse surrounding drug use, and they create a tie between the Harm Reduction movement and movements that seek to build a stronger apparatus for the provision of safety. Primarily, I am writing about this because of the terrific amount of confusion that exists with regards to the concept of abolition, and its contextual relationships with 8cantwait and police reforms. This is intended to serve as a highly simplistic summary of the differences between reformists and abolitionists, and, most importantly, provide access to information and resources for learning and education. Below I have listed several essential resources, which I am using in order to improve my own knowledge and understanding. IHRC has fostered critical conversations since 2016 – conversations that aim to be honest, real, and open to all. If you’d like to join an active conversation about abolition, you may wish to head over to our instagram account and let us know your thoughts on abolition, reform, and more.

The only resource you’ll ever need: an extraordinarily comprehensive guide to learning about prisons, police, and punishment.

Alex Vitale is a Professor of Sociology at Brooklyn College in New York. His 2017 book, The End of Policing, reveals the origins of modern policing as a tool of social control and documents the expansion of police authority. Taking a global perspective, Vitale reviews the many varied forms of policing and explores the alternative systems that communities around the world have created in order to respond to homelessness, sex work, drug use, gang violence, undocumented border crossings, mass shootings, school-based violence, and more.

Vitale’s book is currently available for free in PDF form from the publisher.

For those who aren’t able to invest in reading a full book on the topic, Vitale has given many interviews and published many op-eds in recent weeks:

- Would Defunding the Police Make Us Safer? – via The Atlantic:

- How Much Do We Need the Police? – via NPR

- ‘Defunding the police’ isn’t simply about taking money away, and this book explains it – via SF Gate

- What a World Without Cops Would Look Like – via Mother Jones

Much of the thinking about how communities should respond to this moment lies in the writings of two women and one of their students.

- Angela Davis, the famous activist and scholar, writes about an adjacent but relevant institution in her book, “Are Prisons Obsolete?”

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore is a close friend of Davis’ and a slightly less famous contemporary. Her work is profiled in an excellent New York Times Magazine article from 2019

- Finally, Michelle Alexander is a student of Davis and Gilmore, and her now classic book, The New Jim Crow, is a legal history that gives context to the current questions before us regarding what to do with police, prisons, and more.

IHRC welcomes your thoughts and feedback on the concepts presented in these writings at any time. Please get in touch at hello@iowaharmreductioncoalition.org.

Police Violence & Anti-Black Racism: A Statement from the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition

Black lives matter.

An opinion. A radical political ideology. An example of “reverse racism.” The name of a terrorist organization. For far too many people, these three simple words are capable of invoking responses ranging from indifference to outright hostility. And yet, from the beginning, the words Black Lives Matter have meant simply this: the lives of Black people have value and meaning.

From the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota, Tony McDade in Florida, Breonna Taylor in Louisville and Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, recent events have spurred protest and catalyzed a national conversation about anti-Black racism. While these four deaths are some of the most recent and the most public, they are certainly not the only killings which Black communities are grieving and responding to in this moment. After reading a letter written by the President of Emerson College, I wondered if the 8 minutes that it took for a police officer to kill George Floyd just exceed the number of minutes that make up a person’s “lifetime bandwidth” to witness and experience dehumanization, brutalization, and injustice perpetrated by white people. 8 minutes is just enough time to review a mental film reel of lynchings, murders, and Black death: Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Emmett Till. Sandra Bland. Freddie Gray. Tamir Rice. Eric Garner. Whatever “storage space” that must exist within a collective group of human beings to hold trauma and grief appears to, finally, be full. The anguish reflected in the events of past weeks suggests that for Black Americans, enough is enough. No capacity remains to process another loss of Black life. These aforementioned events also remind us of the lengths that white people will go to in order to protect the social order in which we experience dominance. It is abundantly clear that we have chosen to prioritize our own comfort, protection, and ease over a fundamental respect for Black life.

The violence perpetrated by law enforcement officers in past weeks is alarming. The arrests of journalists along with the brutal assaults on crowds peacefully demonstrating or individuals simply going about their daily lives, is an expression of the polices’ desire to maintain dominance and white supremacy. But it is not necessarily a new phenomenon. Policing is an institution with its roots in anti-Black racism. It is well known that America’s initial police forces were slave catchers, and these militias evolved into a profession that serves as the protectorate for the wealth and property of white people. While today the police are charged with protecting the safety of all individuals in a community, it is reasonable that an institution with its roots in such a history may not necessarily be one without bias, or that is capable of fulfilling this charge.

The statements in the paragraph above have long been viewed as “too dangerous” or “too fringe” for organizations to endorse, especially in Iowa. But a willingness to speak truthfully about the vestiges of slavery, and their impacts today, is reflected in recent statements from the nation’s leading health care and public health organizations: In a statement released last week by the American Medical Association (AMA), titled, “Police brutality must stop,” the most influential entity representing physicians in the U.S. recognized that while many who serve in law enforcement are committed to justice, police violence is a striking reflection of the American legacy of racism. The AMA outlined a growing body of medical research that documents the significant race-based disparity in experiences with police violence and noted that such experiences are linked to adverse chronic health outcomes for all Black people. Police violence results in higher levels of chronic stress among Black Americans, which manifests in worse mental health outcomes and is embodied through shorter life expectancies. This tells us that policing is simply not an institution that can create or ensure safety for Black communities.

At the same time, it is necessary that I recognize the humility and thoughtful leadership that are demonstrated in statements from Iowa’s law enforcement community on the killing of George Floyd. In particular, statements from the Iowa Police Chiefs Association and from Sgt. Brad Kunkel (the winner of yesterday’s Democratic primary election for Sheriff in Johnson County) model a preference for de-escalation and a willingness to engage in dialogue, even when it is uncomfortable. There are highly varied relationships between community members and their law enforcement institutions across the state. The vast majority of individuals who work in Iowa’s law enforcement professions do so because of a commitment to the belief that our world can be transformed into one that establishes safety for all. While we may at times disagree on the specific tactics or policies that are necessary or effective, I believe that all of our work can ultimately be united in the desire to create communities where everyone can experience peace, freedom, and joy. For this reason, IHRC is committed to building relationships with all community members and leaders, including individuals employed by law enforcement agencies, across our state. Since 2016, we have maintained a desire and willingness to engage in conversations with law enforcement that allow everyone to be fully seen.

As communities examine the role of racism in the justice system and beyond, the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition is responding to these events and the resultant calls to action from Black leaders. We, in turn, call on our elected leaders to publicly and deliberately engage with the requests for structural change, divestment in law enforcement institutions, and investment in safety, wellbeing, and healing for Black communities.

The purpose of this statement and call to action is three-fold:

First

To offer the briefest of responses to those Black folks who we live and work alongside and who are our colleagues, clients, patients, acquaintances, dear friends, service providers, neighbors, strangers, mentors, writers, friends’ babies, elected officials, celebrities, teachers, lovers, healers, sisters, brothers, children: you are heard. Both in your expressions of anguish and insistence that real, lasting, structural change happen, and that it happens not in a month or in a year, but now.

Second

To offer a statement that is primarily directed towards white people (particularly and especially those living in Iowa) that articulates Harm Reduction’s ideological relationship with racial justice and anti-racism work; highlights, in Floyd’s killing, the invocation of a process of dehumanization that is deeply intertwined in policies that criminalize drugs; and invites engagement, partnership, and accountability in IHRC’s work.

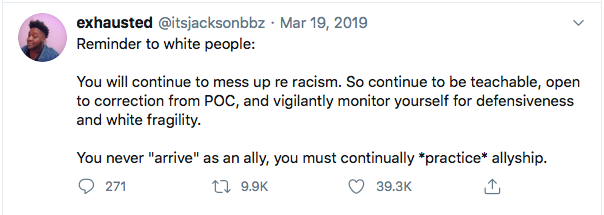

As a young organization, we are committed to receiving and responding to feedback as it concerns the themes discussed above and in the coda that follows. Perhaps most importantly, we understand that as an organization that is founded and led by white people, just as much of the work to be done concerns our own processes, strategies, and operations, which we will continue to share information about publicly. We affirm the idea that anti-racism is not a destination, and that as white people we will never become un-racist. A few days or weeks of training and reading may facilitate personal growth, but does not undo a culture that has been built over the course of many centuries. As such, we are engaged in a constant process of conversation, learning, and growth, and I fully expect that our attempts at ally-ship will at times be imperfect and at others potentially ill-informed. It is for this reason that I welcome the opportunity to receive feedback, and invite you to share your thoughts. And whether that be in a week or in two years, the prioritization of accountability is sincere

Third

To urge local leadership to consider the aforementioned statements from the American Medical Association, the Drug Policy Alliance, the American Public Health Association, and the specific calls to action from those leaders who affirm that Black Lives do Matter and entertain this question: Can our community guarantee: not one more loss of Black life at the hands of police? In responding to this question, it is critical that elected leaders steer away from the allure of reforming the current system through tactics that are well known to be ineffective, like implicit bias trainings, early warning systems for poor conduct, or civilian review boards. While none of these tools are inherently evil, the current moment makes clear that an institution cannot be reformed if it was never meant to protect Black lives in the first place.

During the month of June, IHRC will be sharing a number of updates, events, and projects that connect to the topics and themes in this statement. While the majority are previously planned and part of our ongoing work that relates to criminal justice reform, drug policy advocacy, and the provision of drug user health services across a number of Iowa communities, several initiatives are planned as part of our internal and external response to the events that have occured in the past week.

To echo the sentiments conveyed above, I invite you to contact me at sarah@iowaharmreductioncoalition.org at any time. Please feel free to reach out with your questions, thoughts, or concerns.

Sincerely,

Sarah Ziegenhorn

Founding Executive Director

Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition

Coda: A Deeper Dive

At the Intersection: Harm Reduction & Racial Justice

In the events leading up to the killing of George Floyd and in the public conversation held in the aftermath of his death, drug use has played an often subtle but critical role. This comes as no surprise, given the way in which drug use is meant to establish deviance and indicate poor moral character. As Floyd was held to the ground by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, another police officer looks on and states to a crowd of youth who were gathered nearby, watching and filming the encounter, “This is why you don’t do drugs, kids.” Earlier in the encounter, another officer and Chauvin discuss “excited delirium,”a term that is not recognized in medicine and has been historically used in law enforcement settings to describe alterations in consciousness and mental status attributable to poly-drug use, as well as establish a cause for sudden death while in police custody. The term is controversial and many in medicine believe that it is used as biological justification for deaths among Black men that result from police violence. In the criminal complaint associated with his death, a press release summarizing a forensic report asserts the idea that his death may not have been the result of police force, but rather by drug use: “The combined effects of Mr. Floyd being restrained by the police, his underlying health conditions and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death.” In the results from an autopsy ordered by Floyd’s family, released today, Floyd’s cause of death is listed as asphyxiation due to compression of nerves in his back and neck. In all of these moments, we are led to believe that George Floyd’s death is a reasonable or expected outcome for someone who may possess or use drugs. Kassandra Frederique, the incoming Executive Director of the Drug Policy Alliance summarizes the meaning of these references to drug use:

“With George Floyd most recently, Breonna Taylor earlier this month, and countless others before them, perceived drug possession and drug use served as a justification by law enforcement to dehumanize, strip dignity from, and ultimately kill people of color.”

In a statement from the Drug Policy Alliance, released late last week, Kassandra Frederique states why the work to reform drug policy is fundamentally linked with the work for racial justice:

“Drug involvement–whether perceived or real–has provided a convenient excuse for these violent and too often fatal law enforcement interactions. [We must] continue fighting to remove drug involvement as a cover for disregarding the dignity and sanctity of human life. And we will challenge and hold these institutions accountable. We refuse to stand by while another person cries out, as Eric Garner and George Floyd did, “I can’t breathe,” as law enforcement ends their life.

Ending the failed war on drugs will not legalize Black people, but it will disrupt a system that chips away daily at the very core of our humanity. We don’t need symbolic gestures, we need to strategize, organize, and build campaigns to ensure this doesn’t happen again. We stand ready to work with our allies to do our part.”

The War on Drugs & George Floyd Collide

Harm Reduction is an ideological approach to drug use that views the expertise gained through lived experience as paramount. Harm Reduction prioritizes the voices, knowledge, and wisdom of people with lived experience and understands that in order to create communities that are healthy, safe, and whole, the people who are directly impacted must be centered and intimately involved in decision making, policy development, and program implementation. With regards to substance use, we understand that people who use drugs (PWUD) expect to be engaged in the creation of any policy or program that is meant to serve or improve the lives of PWUD. Thus, we recognize the fundamental importance of centering the voices and expertise of Black people in decision-making (of any kind and at all levels) that concerns the conditions in which Black Americans live, including but not limited to racism and the legacy of slavery as an institution.

Harm Reduction is also a social movement and community of people working for justice, dignity, freedom, and respect for the people who use illicit, psychoactive drugs. We know that the lives of PWUD are deeply impacted by the laws under which these drugs are regulated, and that the origins of these regulations are deeply intertwined with late 19th century / early 20th century ideologies regarding race and power. Simply put, many of the race-based disparities that exist today in overdose deaths, HIV rates, arrests, sentencing lengths, and recidivism rates are the outcome of a legal framework that has assigned meaning to classes of drugs by connecting their use with racial and ethnic identity as a means of establishing and perpetuating deviance. The state has carefully cultivated the propaganda that drug use begets deviance, violence, and disorder thus begets a system in which those people who use drugs must be regulated, policed, and controlled in order to reduce violence, deviance, and disorder for the broader collective to be guaranteed safety.

Here is a fundamentally important point: While there are obvious parallels between the struggles and institutional hostility faced by PWUD and BIPOC, we are in no way claiming equivalency between the two, only highlighting that the similarities provide motivation and strengthen our desire to work to dismantle the legacy of white supremacy and entrenched racism.

Harm Reductionists recognize that our day to day work is often technical and focused on minimizing risks for adverse health outcomes at multiple scales, from training individuals to administer a medication that may save their life in the event of overdose, to debating the minutiae of the language in a bill that proposes minor revisions to the Iowa code. Yet we also know that this work is also deeply symbolic. Our sustained commitment is reflective of the belief in a much larger vision for what our communities could one day look like. This work is thus done in service to the idea that a world is possible where institutions and individuals engage with one another through relationships of support, healing, joy, and care, rather than punishment, authority, shame, or violence. In other words, it is to say that we fundamentally connect our work to racial justice, and know that to transform the way our world engages with drugs and the people who use them also means to transform the way we engage with Black lives and value assigned to them.

IHRC May 2020 Volunteer of the Month: Spotlight on Mitchell Hooyer

Since 2016, IHRC has trained over 500 volunteers from across Iowa to become harm reduction advocates and direct service providers. Maintaining nearly 100 active volunteers in our program at any one time, the individuals who dedicate their time, energy, thoughtfulness, and talents to IHRC give the organization its strength and staying power. Volunteers provide support at nearly every level of IHRC's program, from late night naloxone deliveries for clients to trips across the state to meet with legislators in their homes. Each month, the IHRC community recognizes one individual for their commitment to advancing drug user health in Iowa. Through the "Volunteer of the Month" Award, our community honors the contributions and impact a particular individual has made. While this award has been given since 2017, as of mid-2020 we're taking the recognition public and sharing our monthly awardee with the wider audience engaged with our work. Each winner is recognized with either a gift from IHRC's merch shop or a Harm Reduction book of their choosing. Please join us in celebrating the contributions these individuals make to our communities, and the entire state of Iowa, each day.

Mitchell Hooyer

Mitchell is a medical student at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine with one year left before entering an Emergency Medicine residency. He’s a native Iowan who grew up on a cattle farm in Northwest Iowa and went to college at Drake University in Des Moines where he majored in Biology and Bartending. Mitchell has been with IHRC since 2018, volunteering in a variety of positions including street outreach, operating the Central Iowa hotline and delivery service, working the Cedar Rapids front desk, planning webinars, and most recently starting a student harm reduction interest group at the University of Iowa. Outside of IHRC and school he enjoys reading (check out IHRC’s forthcoming blog post for recommendations), playing volleyball, and buying too many new plants.

Mitchell has been a volunteer with IHRC since beginning medical school in Iowa City and applied to volunteer in January 2018, training that spring. Over the past 2.5 years, Mitchell has become one of our program’s key team members. While living in Des Moines from January – December 2019, Mitchell worked closely with Deborah (IHRC’s Central Iowa Program Manager) and took care of the hotline + client deliveries on a weekly basis. He also has become immersed in the broader harm reduction field and has a clear passion for the individuals we work with & the community we serve. This passion is made visible by the curiosity he brings to this work; his commitment to learning; a consistent engagement with new resources and materials; and the way in which his knowledge-base seems to grow exponentially with regards to: a) client experiences, goals, challenges, and needs; b) the inner-workings of health, social, and criminal-legal systems and how these systems impact people via the production of structural forces; c) research publications, thought leaders, critical organizations, and experts in the field; and d) traditional news media content, books, social media content, and more. Mitchell returned to Iowa City in January and has spent the last two months running the front desk in the office on Monday and Wednesday afternoons. While the office has been unusually quiet due to COVID-19, Mitchell has also used his time to develop a number of other projects. Recognizing the need for new initiatives, organizations, and structures that can approach harm reduction work from different perspectives, Mitchell has put together the Harm Reduction Interest Group for Medical Students, which will liaise with the national group of a similar name. This group will be able to expand opportunities for training and education in drug user health for all medical students. Mitchell has developed a structure for the group that is highly strategic, uniquely well organized, and sets the group up for success in the short, medium, and long term future. Mitchell is currently working on a number of other projects within IHRC, including the summit and the COVID-19 research project. As a grassroots organization whose strength comes directly from the leadership and engagement of all participants within the group, IHRC is significantly better off because of Mitchell’s commitment to the work we do, and because of the enjoyment and meaning that he derives from it and brings to it. Thanks so much Mitchell, for all of the work you have put in over the past two years, and for all of the good things you have planned for the next year!

Nation’s Leading Drug Policy Experts Demand Medication Assisted Treatment and COVID-19: Treatment Reforms

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical to remember that we are still in the midst of an overdose crisis.

While many regulators have argued that methadone and buprenorphine policies must be deliberately restrictive due to the risk of overdose, adverse medication effects, and medication diversion, the COVID-19 crisis has forced many regulating bodies to re-evaluate these policies in order to comply with the urgent need for communities to practice social distancing and sheltering-in-place. Multiple government agencies including SAMHSA, the DEA, Medicare, and Medicaid have recently announced policy changes to allow for more flexible prescribing and dispensing. While these changes are a step forward, clinics have been either reluctant or resistant to fully implement them to the extent allowable under law. In light of the evolving pandemic and the needs of the community, we must not allow fears of overmedication and diversion to outweigh the health risks caused by patients being forced daily to congregate in large groups, or being driven to an adulterated illicit drug supply.

Close person-to-person contact and group assembly are currently actions deemed hazardous to public health. Unfortunately, “sheltering in place” is unrealistic for many people who use drugs. People who use opioids are either forced to continue to engage with the illicit drug market or must comply with prohibitive and insurmountable requirements to receive medications for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). Many opioid users are at an increased risk of COVID-19 infection due to being immunocompromised and/or having comorbid health conditions.

In order to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection, involuntary withdrawal, and drug poisoning, the Urban Survivors Union and the undersigned organizations strongly recommend the following measures be taken immediately:

1) The only acceptable standard for discharge of patients from OUD treatment during the COVID-19 outbreak shall be violent behavior that would endanger their own health and safety or that of other patients or staff.

2) Administrative detox shall be fully suspended during the pandemic and patients shall be provided the opportunity to request dose increases as needed, given that the illicit drug market will continue to experience fluctuations and patients need access to these life-saving medications. Patient doses shall not be reduced during the transition to take-home care unless they request adjustments to their doses, or documented medical emergencies require it and patients cannot consent due to medical crises, as may be the case with severe respiratory distress resulting from COVID-19 infection.

3) Referrals for COVID-19 testing shall be made available at all opioid treatment programs (OTPs), as well as syringe service programs. Staff shall receive training to recognize the symptoms of COVID-19 and be familiarized with protocols to refer patients for further testing. Harm reduction providers can also play an essential role in “flattening the curve” of transmission by identifying cases, making medical attention available to those who test positive, and teaching life-saving harm reduction skills to help people stay safe during this crisis. Plain language and evidence-based public health materials about COVID-19 prevention, symptom identification, and treatment should be available in locally prominent languages at all locations for participants and their communities.

4) During the COVID-19 national emergency, healthcare professionals–including doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists–shall not be required to complete the previouslymandated training and waiver to prescribe these medications, thereby making MAT available in all settings. Prescribers shall not have limitations on the number of patients that they can treat. Naloxone and other overdose prevention tools (i.e. fentanyl test strips) shall be prescribed or made available with all dispensed medications in compliance with state law.

5) Opioid treatment programs (OTPs), prescribing clinicians, and pharmacies shall actively work to expand access to methadone treatment through the medical maintenance/office-based and pharmacy-delivery methods currently allowed by federal exception/waiver. The existing OTP regulations for the dispensing of MAT shall be temporarily adjusted to require all pharmacies to dispense these medications. This will reduce the risks of transmission associated with daily clinic attendance and person-to-person contact. In accordance with SAMHSA recommendations, lockbox requirements for take-home dispensing shall be suspended. Standard dispensing protocols for other opioid medications are deemed sufficient, since child- and tamper-proof bottles are already in use for methadone and buprenorphine. (Per SAMHSA’s TIP 43, Chapter 5: “Some programs require www.ncurbansurvivorunion.org 3 patients to bring a locked container to the OTP when they pick up their take-home medication to hold it while in transit. This policy should be considered carefully because most such containers are large and visible, which might serve more to advertise that a patient is carrying medication than to promote safety.”)

6) Take-home exception privileges shall be expanded to the maximum extent possible, limited only by available supply and operations for delivery. Any bottle checks that clinics wish to conduct shall be conducted by tele-medicine. Take-home schedules shall be authorized for individuals in all medical settings, including pharmacies and mobile vans. In light of new SAMHSA guidelines, clinics shall allow 14 to 28 days of take-home privileges to as many patients as possible. Patients testing positive for benzodiazepine or alcohol use shall be allowed the take-home privileges outlined in SAMHSA guidelines, but may be additionally required to check in via telemedicine for the purpose of decreasing the risk of adverse reactions, including overdose. Access to take-home doses is critical to keep patients engaged and retained in treatment.

7) Telehealth and service by phone shall replace any and all in-person requirements and appointments as the primary means of service provision until social distancing guidelines change. Toxicology requirements shall be suspended for the duration of telehealth-based services. Telemedicine services shall include waivered platforms, such as telephone intakes and video conferencing, as some patients may have different access needs.

8) The regulatory in-person requirements for methadone inductions shall be lifted in order to be consistent with the new policy changes for buprenorphine inductions. Clinic-based in-person appointments shall conform to social distancing requirements and OSHA guidelines for the management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

9) DEA restrictions on mobile medication units shall be revised to accommodate delivery of medications to individuals who are sequestered in their homes, are quarantined, or live in rural communities that are 15 miles or more from the nearest opioid treatment program.

10) State and federal Medicaid dollars shall be expanded to cover all costs for take-home medications not otherwise covered by insurance for patients experiencing financial hardship due to COVID-19. In states that did not expand Medicaid, the state shall be the payor of last resort.

In the interest of saving lives and adhering to existing public health protocol for management of COVID-19 transmission, it is necessary to make significant revisions to existing regulatory standards. This is a critical time to take decisive action for the protection of patients, providers, their families, and the community. As our healthcare system reaches full capacity and becomes overburdened by COVID-19-related emergencies, as seen in Italy and Spain, providers on the front lines will be forced www.ncurbansurvivorunion.org 4 to make life and death choices. These recommendations outline a plan of primary prevention that will minimize the burden on our healthcare system and save lives during this national emergency.

We, the undersigned, are a coalition of direct service providers, community advocates, public health officials, medical professionals, human rights groups, people in recovery, treatment professionals, members of impacted communities, and many others. We ask SAMHSA, the DEA, and all other federal, state, and local regulatory bodies and health authorities to adopt these recommendations fully and immediately in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Organizations

Urban Survivors Union

Louise Vincent, MPH

Executive Director

National Harm Reduction Coalition

Monique Tula

Executive Director

The National Alliance for Medication-Assisted Recovery

Zachary Talbott, MSW

President

Joycelyn S. Woods, MA

Executive Director

Faces and Voices of Recovery

Patty McCarthy, M.S.

Chief Executive Officer

National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable

Lauren Canary, MPH

Director

Law Enforcement Action Partnership

Major Neill Franklin (Ret.)

Executive Director

The Levenson Foundation

Benjamin A. Levenson

Chairman

Foundation for Recovery

Dona M. Dmitrovic, MHS

Executive Director

National Council for Behavioral Health

Chuck Ingoglia

President and CEO

305 Psychotherapy Group

Mark Houston, LCSW

Owner and Psychotherapist

Addiction Professionals of North Carolina

Sarah Potter, MPA

Executive Director

AIDS United

Drew Gibson, MSW

Policy Manager for HIV & Drug User Health

Alcohol & Drug Abuse Certification Board of Georgia

Amanda Finley

Executive Director

Alliance for Positive Health

Diana Aguglia

Regional Director

The BALM Training Institute for Family Recovery Services/Family Recovery Resources

Beverly A Buncher, MA, CBFRLC, PCC

Chief Executive Officer

Bay Area Workers Support

Maxine Holloway, MPH

Co-Founder

Benevolence Farm

Kristen Powers

Interim Executive Director

Better Life in Recovery/Springfield Recovery Community Center

David Stoecker, LCSW

Executive Director

BioMed Behavioral Healthcare, Inc

Brian A McCarroll DO. MS. ABAM

CEO, President

Choices Recovery Trainings

Ginger Ross, CRSW, NCPRSS

Owner/Trainer

Church of Safe Injection

Kari Morissette

Director

Circle for Justice Innovations

Aleah Bacqui Vaughn

Executive Director

City of Revere – Substance Use Disorder Initiatives Office

Julia Newhall, BSW, CPS

Director

Coastal Holistic Care

Jessi Ross

Founder

Connecticut Certification Board

Jeff Quamme, MSW

Executive Director

DanceSafe

Mitchell Gomez

Executive Director

Desiree Alliance

Cristine Sardina, BWS, MSJ

Director

društvo AREAL

Janko Belin

President

ekiM For Change

Diannee Carden Glenn

Director

Grayken Center for Addiction, Boston Medical Center

Michael Botticelli, MEd

Executive Director

Greater Hartford Harm Reduction Coalition Inc.

Mark A. Jenkins

Executive Director

Guilford County Solution to the Opioid Problem

Chase Holleman, LCSW, LCAS

Program Director

Harm Reduction Action Center

Lisa Raville

Executive Director

Harm Reduction Ohio

Dennis Cauchon

President

Harm Reduction Therapy Center

Jeannie Little, LCSW

Executive Director

Health in Justice Action Lab

Leo Beletsky, JD MPH

Director

Health Professionals in Recovery

William C. Kinkle, RN, EMT-P, CRS

Co-Owner

Health Services Center, Inc.

Melissa Parker

Prevention Projects Director

Healthy Streets / Health Innovations

Mary Wheeler

Program Manager

Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition

Sarah Ziegenhorn

Executive Director

Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice

Gabriel Sayegh, MPH

Co-Executive Director

The Lemire Group LLC

Dean Lemire

Owner

Lifespan Counseling

Dene Berman, Ph.D., MPH, ABPP, MAC

Director

Lysistrata Mutual Care and Collective Fund

Cora Colt

Co-Founder and Treasurer

MEDPEARL LLC

Deanna Dunn, PharmD

Owner/Pharmacist

The Middle East and North African Network of/for People who use Drugs

Hasan Taraif

Executive Director

Minnesota Recovery Connection

Wendy Jones

Executive Director

Movement for Family Power

Lisa Sangoi and Erin Coud

Co-Founders and Co-Directors

NCADD- NJ

Heather Ogden, CPRS, CRSP, CADC Intern

Advocacy Coordinator

Northern Berkshire EMS

Stephen Murray, BBA, NRP

Paramedic Supervisor

ONESTOP Harm Reduction Center, North Shore Health Project

Mary Doneski, MA

Program Manager

PeerNUPS/Athens/Greece

Christos Anastasiou

Coordinator

Pennsylvania Alliance of Recovery Residences

Fred Way, MA

Executive Director

Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition

Devin Reaves, MSW

Executive Director

People’s Action

Sondra Youdelman

Campaigns Director

The People’s Harm Reduction Alliance

Shilo Jama

Executive Director

The Perfectly Flawed Foundation

Luke Tomsha

Executive Director

Philadelphia Drug Users Union

David Tomlinson, BA

Founder

Sex Workers Organizing Project- USA

Christa Daring

Executive Director

The Southern Tier AIDS Program

John Barry, LMSW

Executive Director

Students for Sensible Drug Policy

Betty Aldrich

Executive Director

Students For Sensible Drug Policy Africa

Ewelle Sylvester Williams, SW

Vice Chairman

Substance Use, Policy, Education and Recovery

PAC

Haley McKee

Co-Chair

Suncoast Harm Reduction Project

Julia Negron, CAS

Founder and Lead Organizer

Tennessee Recovery Alliance

Sara Alese

Executive Director

Texas Drug User Health Alliance

Mark Kinzly

Executive Director

Texas Harm Reduction Alliance

Joy Rucker

Executive Director

Voices of Community Activists and Leaders New York

Jeremy Saunders

Executive Director

Whose Corner is it Anyway

Caty Simon

Founding Co-Organizer

Women With A Vision

Christine Breland Lobre, MHS, MPH, LPC

Program Director

Zanzibar Network of People Who Use Drugs

Kassim Nyuni

Executive Director

Drug Policy Alliance

Kassandra Frederique

Managing Director, Policy Advocacy &

Campaigns

International Certification & Reciprocity

Consortium

Crystal Smalldon, CCAC, CIAC, RSSW

President

Behavioral Health Association of Providers

Pete Nielsen, MA, LAADC

CEO

Center on Addiction / Partnership for DrugFree Kids

Frederick Muench, Ph.D.

President

National Advocates for Pregnant Women

Lynn M. Paltrow, J.D.

Founder and Executive Director

Recovery Advocacy Project

Ryan Hampton

Organizing Director

Open Society Foundations

Sarah Evans

Unit Manager, Public Health Program

Kasia Malinowska-Sempruch

Director, Global Drug Policy Program

Brave Technology Coop

Gordon Casey

Chief Executive Officer

Broken No More

Tamara Olt, M.D.

Executive Director

CADA of Northwest Louisiana

Bill Rose, LAC, CCS, CCGC

Executive Director

C4 Recovery Foundation, Inc.

Ricard Ohrstrom, Chairman

Jack O’Donnell, CEO

Center for Optimal Living

Andrew Tatarsky, Ph.D.

Executive Director

Center for Popular Democracy/ Opioid Network

Jennifer Flynn Walker

Senior Director of Advocacy and Mobilization

Central Texas Harm Reduction

Richard Bradshaw

Community Outreach Leader

CheckUpandChoices.com

Reid K Hester, Ph.D.

Director, Research Division

Chicago Drug Users Union

Peter Moinichen, CADC, CODP, MAATP

Co-Founder

Chicago Recovery Alliance

Brandie Wilson

Executive Director

Exponents, Inc.

Joseph Turner, J.D.

President and CEO

Faith In Public Life

Blyth Barnow, MDiv

Harm Reduction Faith Manager

Families for Sensible Drug Policy

Carol Katz-Beyer

President

Florida Opiate Coalition- Block by Block

Bonny Batchelor

Director

Foundation for Recovery

Dona M. Dmitrovic, MHS

Executive Director

Full Circle Recovery Center, LLC

Stephanie Almeida, CDAC

Founder

Georgia Overdose Prevention

Laurie Fuggitt, RN and Robin Elliott, RN

Co-Founder

GoodWorks: North Alabama Harm Reduction

Morgan Farrington

Founder

The Grand Rapids Red Project

Stephen Alsum

Executive Director

HIPS

Tamika Spellman

Policy and Advocacy Associate

HIV/HCV Resource Center

Laura Byrne, MA

Executive Director

Hope Recovery Resources

Beth Fisher Sanders, LCSW, LCAS, MAC, CCS, MATS

Chief Executive Officer

HRH413

Albert Park, MSW

Co-Founder

International Network of People Who Use Drugs

Judy Chang

Executive Director

Illinois Association of Behavioral Health

Sara Howe, MDA

Executive Director

Inclusion Recovery

Dan Ronken, LPC, LAC

Founder

Indiana Recovery Alliance

Kass Botts

Executive Director

Innovative Health Systems

Ross Fishman, Ph.D.

President

Instituto RIA

Zara Snapp

Co-Founder

New England Users Union

Jess Tilley

Executive Director

New Jersey Harm Reduction Coalition

Jenna Mellor

Executive Director

A New PATH, Parents for Addiction Treatment & Healing

Gretchen Burns Bergman

Executive Director

New View Addiction Recovery Educational Center

Jennifer A. Burns, MA

Executive Director

New York Center for Living

Audrey Freshman, Ph.D., LCSW, CASAC

Executive Director/Chief Clinical Officer

New York State Harm Reduction Association

Joseph Turner, J.D.

Co-Chairperson

North American Syringe Exchange Network/Tacoma Needle Exchange

Paul A. LaKosky, Ph.D.

Executive Director

North Carolina Harm Reduction

Shelisa Howard-Martinez

Executive Director

North Carolina Survivors Union

Louise Vincent, MPH

Executive Director

Project Point Pittsburgh

Alice Bell, LCSW

Overdose Prevention Project Coordinator

Protect Families First

Annajane Yolken

Executive Director

Provenance Counseling

Lisa S Musarra, MSW, LCSW, LCADC, ICADV

Owner

The Reach Project, Inc and Reach Medical, PLLC

Justine Waldman, MD, FACEP

Chief Executive Officer

Reframe Health and Justice

Sasanka Jinadasa

Partner

Rights & Democracy NH, Rights & Democracy VT, Rights & Democracy Institute

Kate Logan, MA/ABD

Director of Programming & Policy

R Street Institute

Carrie Wade, Ph.D., MPH

Director of Harm Reduction Policy

Chelsea Boyd, MS

Research Associate Harm Reduction Policy

San Francisco AIDS Foundation

Laura Thomas, MPH, MPP

Director of Harm Reduction Policy

The Seven Challenges LLC

Robert Schwebel, Ph.D.

Author and Program Developer

Sex Worker Advocacy Coalition

Tamika Spellman

Lead Organizer

Sex Workers Outreach Project Behind Bars

Jill McCracken, Ph.D.

Co-Director

Texas Harm Reduction Conference

Emily Gray

Co-Founder

Texas Overdose Naloxone Initiative

Mark Kinzly

Executive Director

Truth Pharm

Alexis Pleus

Executive Director

Ukrainian Network of People who Use Drugs

Anton Basenko, ME

Chair of the Board

University of Missouri, St. Louis Missouri Institute of Mental Health

Claire Wood, Ph.D.

Rachel Winograd, Ph.D.

Addiction Science Faculty

Urban Survivors Union, Greensboro Chapter

Derek McCray Miller

Member

Dr. Vando Medical Services

Leonardo Vando, MD

Chief Executive Officer

Vantage Clinical Consulting LLC

Jamelia Hand, MHS, CADC, CODP

Chief Executive Officer

Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform

Thomas Dalton, J.D., MA, LADC

Executive Director

VICTA

Lisa Peterson, LMHC, LCDP, LCDS, MAC

Chief Operating Officer

Individuals: Professionals

Michelle Accardi-Ravid, Ph.D., Clinical Psychologist, Acting Assistant Professor, University of Washington Medical Center/ Harborview Medical Center

Chris Alba, Harm Reduction Specialist, Health Innovations Inc

Onyinye Aleri, Case Manager, Charm City Care Connection

Sarah Baranes, MD Candidate

Anton Basenko, ME, Country Focal Point: PITCH, Alliance for Public Health

Donna Beers, MSN, RN-BC, CARN, Boston Medical Center

Leo Beletsky, J.D., MPH, Health in Justice Action Lab, Northeastern University Patricia Bellucci, Ph.D., Clinical Psychologist/Psychoanalyst

Daniel Bibeau, Ph.D., Professor of Public Health Education, University of North Carolina, Greensboro

F. Michler Bishop, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Director, Alcohol and Substance Abuse Services, Albert Ellis Institute, NY

Ricky N. Bluthenthal, Ph.D., Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California

Elizabeth Bowen, PhD, Assistant Professor, University at Buffalo School of Social Work

Jennifer J. Carroll, Ph.D., MPH, Assistant Professor, Elon University

Sharon Chancellor, CSAC

Aaron Ferguson, The Social Exchange Podcast

Anna Fitz-James, MD, MPH

Kathleen Foley, PhD

Ryan Fowler, CRSW, Harm Reduction Program Coordinator, HIV/HCV Resource Center

Graeme Fox, Sonoran Prevention Works

David Frank, MMT Sociologist, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, New York University

Meryl Freedman, M.Ed, Families for Sensible Drug Policy

Ann Fuqua, BSN

Carmen Albizu Garcia, MD

Angie Geren, APP, CHt, Arizona Recovers

Louisa Gilbert, Co-Director, Social Intervention Group

Scott Goldberg, MD, Montefiore Medical Center

Judith R. Gordon, Ph.D., University of Washington

Traci Green, Ph.D., MSc, Opioid Policy Research Collaborative, the Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University

Jennifer L Kimball, Berkshire Opioid Addiction Prevention Collaborative

Bethea Kleykamp, MA, Ph.D., Research Associate Professor, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry

Gary Langis, Harm Reduction Specialist, Boston Medical Center

Bethany Medley, MSW, Adjunct Lecturer, Columbia School of Social Work

Rosie Munoz-Lopez, MPH, Research Community Engagement Facilitator, Boston Medical Center

Janie L Kritzman, Ph.D., Lic. Psychologist, Psychological Associates, MA; NYSPA, Addiction Division

Dana Kurzer-Yashin, Overdose and Harm Reduction Trainer, Harm Reduction Coalition

David Lucas, MSW, Clinical Advisor, Center for Court Innovation

Samuel MacMaster, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Health, Baylor College of Medicine

Priya Mammen, MD, MPH, Physician, Kensington MMT Clinic

Marilena Marchetti, Co-Director, Liquid Handcuffs

Bayla Ostrach, MA, PhD

Steven Pacheco, Program Officer, Circle for Justice Innovations Fund

Ju Nyeong Park, Assistant Scientist, Johns Hopkins University

John P Pasagiannis, Ph.D., Clinical Psychologist

Stanton Peele, J.D., Ph.D., Founder, The Life Process Program

Bonnie A Peirano, MPH, Ph.D.

Sandra F Penn, MD, FAAFP

Kim Powers, Drug User Health Outreach Coordinator, AIDS Support Group Cape Cod

Garrett Reuscher, CASAC, MSW student, Social Intern, Footsteps

Helen Redmond, LCSW, Adjunct Faculty, Silver School of Social Work, New York University, and Co-Director of Liquid Handcuffs

Tina Reynolds, Program Director, Circle for Justice Innovations

Kathran Richardson, PRSS, Potomac Highlands Guild

Lindsay Roberts, MSW, NCSU Board Member and Sex Worker Liaison

Patrick Roff, Curriculum and Training Developer, Prevention is Key/CARES

Gabi Teed, BSW, CRSW, Perinatal SUD Care Coordinator, Amoskeag Health

Matthew Tice, LCSW, Pathways to Housing PA

Denise Tomasini-Joshi, J.D., MIA, Division Director, Open Society Foundations

Bruce G. Trigg, MD, Public Health and Addiction Medicine Consultant

Mary Kay Villaverde, M.S., Board Member, Families for Sensible Drug Policy

Ingrid Walker, Ph.D., Associate Professor, University of Washington, Tacoma

GracieLee Weaver, PhD, MPH, CHES, NBCHWC, University of North Carolina, Greensboro

Steffie Woolhandler, MD, MPH

Tyler Yates, CPSS, CADC-I, Syringe Exchange Program Coordinator, Guilford County Solution to the Opioid Problem

M. Scott Young, Research Associate Professor, University of South Florida

Jon E. Zibbell, PhD, Senior Scientist, RTI International / Emory University

Christie Chandler, MA, QP, North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition

Hong Chen Chung, MD, MPH, Medical Consultant, Community Action Programs Inter-City, Inc

Seth Clark MD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Kelley Cohill, LCSW-C

Susan E Collins, Ph.D., Co-Director, Harm Reduction Research and Treatment Center

Erica Darragh, Board Member, Students for Sensible Drug Policy; Chapter Director, DanceSafe

Jane Dicka, Health Promotion Team Coordinator, Harm Reduction

Victoria Mary Doneski, Program Manager, ONESTOP Harm Reduction Center

Patt Denning, PhD, Director of Clinical Services and Training, Harm Reduction Therapy Center

Cathy Dreifort, Harm Reduction Outreach Specialist, Shot in the Dark

Andria Efthimiou-Mordaunt MSc, Coordinator, John Mordaunt Trust

Nabila El-Bassel PhD, Director, Social Intervention Group

Taleed El-Sabawi, Assistant Professor, Elon University School of Law

Nancy Handmaker, Ph.D., Licensed Psychologist, Addictions Specialist

Jesse Harvey, CIPSS, RCA, Community Organizer, Church of Safe Injection

Jennifer I. Healy, Former Director, Bcbsma, Board Member, The Global Recovery Movement

Robert Heimer, PhD, Professor of Epidemiology, Yale School of Public Health

David Himmelstein, MD

Robert Hofmann, U.S. Movement Building Fellow, Students for Sensible Drug Policy

Heather Howard, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Florida Atlantic University

Sheila Humphrey, Dayton Director, Harm Reduction Ohio

Lauren Jessell, MSW, Senior Research Associate

Sterling Johnson, Esq., Organizer, Black and Brown Workers Cooperative

Carol Jones, Director of Harm Reduction, Alliance for Living

Ashley Jordan, Adjunct Assistant Professor, City University of New York

Sharon Joslin, APRN, Director, Community Health Care Van, Yale University School of Medicine

Norty Kalishman, MD

Mary E. Kelly, PsyD, Psychologist

Stefan Kertesz, MD, Professor, University of Alabama

JoEllen Marsha, MPA, LEAD Program Director, CONNECT

Bethany Medley, MSW, Adjunct Lecturer, Columbia School of Social Work

Regina McCoy, MPH, MCHES, NBC-HWC, Professor, UNC Greensboro

Ryan McNeil, Ph.D., Assistant Professor & Director of Harm Reduction Research, Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, Yale School of Medicine

Nancy Mullin, MA, PsyD Graduate Student, California Institute of Integral Studies

Alicia Murray, DO, Addiction Psychiatrist, General Psychiatrist

Ethan Nadelmann, Founder and former Executive Director, Drug Policy Alliance

Daniel Nauts, MD, FASAM, Consultant/trainer, Montana Primary Care Association

Tammera V Nauts, LCSW, LAC, IBH Director, Montana Primary Care Association

Tracy R. Nichols, Ph.D., Department of Public Health Education, University of North Carolina, Greensboro

Danielle C. Ompad, Ph.D., Associate Professor, New York University School of Global Public Health

Caitlin O’Neill, Director of Harm Reduction Services, New Jersey Harm Reduction Coalition

Dinah Ortiz, NCSU Board Member

Lila Rosenbloom, MSW

Rene R Salazar, Ph.D., MPH, CIH, University of South Florida College of Public Health

Elizabeth A. Samuels, MD, MPH, mHS, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Brown Emergency Medicine

Vanessa Santana, Recovery Coach, Turning Point Recovery Center

Carolyn Sartor, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Yale School of Medicine

Roxanne Saucier, MPH

Jacob Schonberg, CPSS, Social Work Practitioner, UNC School of Medicine Mark Schulz, Associate Professor, University of North Carolina, Greensboro

Mandy Sladky RN, MSN, CARN, Opioid Project Manager and OBOT RN, Public Health Seattle & King County

Samuel Snodgrass, Ph.D., Board Member, Broken No More

Nicole Spector, RN, BSN, Health Innovations Inc

Annie Steinberg, President, GW Chapter Students for Sensible Drug Policy

Dr. Laura Stern, Sage Neuroscience Center

Janet K Stoltenborg, MS, MBA, Member, Moms for All Paths to Recovery from Addiction

Phillip Stracener, NCCPSS, BSW, Harm Reduction Specialist, AIDS Leadership Foothills-Area Alliance

Individuals: Allies

Sarah Beale

Jade Bower

Thomas Butler

Teri Cole-Smith

Elizabeth C. Day

Joseph Dishman

Nora Maria Fuller

Paul Gorman

Melvina Hall

Christie Hansen

Maggie Hart

Anna Herdlein

Emily Jones

Anna Kistin

Coleda Lee

Rivkah L. Meder

Whitney Meex

Bernadette Proctor

Rachel Rourke

Zach Salazar

Michael G. Seay

Kasey Snider

Zabrina Whiting

How to End Overdose: Building Overdose Prevention Programs that Truly Work

Words by Sarah Ziegenhorn

In the past five years, communities across Iowa have put together committees and task forces in order to identify solutions to the overdose crisis.

As a participant in multiple such committees, as well as a consultant providing technical assistance to State Targeted Opioid Response grant recipients (the grant through which the federal government has provided states with money to respond to the overdose crisis), I’ve played a role in developing plans to reduce overdose deaths. More importantly, I’ve also spent the past several years operating an overdose prevention and naloxone distribution program that serves the state of Iowa. Working in four cities and serving the counties surrounding these metro areas (as well as theoretically any Iowa county by mail), the program I direct has distributed nearing 40,000 doses of naloxone since July 1, 2017. Focusing our naloxone distribution on people who use drugs, our program has documented nearly 2,500 reports of overdose reversals. We suspect this number is higher in reality – these are just the individuals who have taken the time to come and tell us that they reversed an overdose with the naloxone we provided to them.

The results of our program are striking. And we believe that they have contributed to the significant decrease in overdose fatalities across the state. Yet, no city, county, or state agency has created a funding opportunity to support the critical life-saving work of our program. We’ve operated on a shoestring budget, selling t-shirts and utilizing volunteer labor, while the federal government has allocated millions of dollars to each state for the overdose crisis response. In the meantime, many community leaders, organizations, researchers, and elected officials have approached IHRC for assistance as they try to understand what strategies will work to end the overdose crisis and build programs based on the best available evidence. Because we routinely field questions from community members about how our program works, why we built it, and what sets of best practices, data, and evidence prop it up, I’ve put together an overdose prevention program starter pak. This set of resources provides some basic information about the history of naloxone access in the United States, and documents the ways in which harm reduction programs have found success in disseminating overdose prevention and response education while blanketing at-risk communities with free, accessible naloxone. This brief post is meant to summarize a few key resources that will help orient community leaders, advocates, elected officials, public health practitioners, researchers, health care providers, and others to the field of overdose prevention and provide a crash-course in what works.

A local paper, The Gazette, reviews comparative findings of one year’s worth of naloxone distribution from community-based organizations and naloxone administrations performed by law enforcement departments. The editorial echos the findings of many of the research studies summarized below: while law enforcement naloxone access can be positive, prioritizing naloxone access for people who use drugs is the most important strategy for making a dent in overdose deaths.

Know Your History: The Origins of Naloxone Distribution

In late 2019, Eliza Wheeler posted an article to Medium, written in celebration of a distribution of 1,000,000 doses of naloxone by harm reduction programs in 2019 and in memory of her late friend and colleague, Dan Bigg. Bigg founded the Chicago Recovery Alliance in the early 1990s and is the driving force around the availability of naloxone outside of hospitals today. While it is now customary for law enforcement officers, EMS, firefighters, and the like to carry naloxone, this is a major departure from the 1990s, when naloxone was a little-known drug relegated to surgical suites and the practices of anesthesiologists. Bigg was a visionary who worked to deregulate this silver bullet and promoted mass distribution of naloxone at the community level. He fundamentally believed that the best people to possess and administer naloxone were people who use drugs themselves, and his theory has proved accurate. Wheeler, who administers a buyers club for harm reduction programs looking to purchase naloxone, has researched naloxone administration in community settings (see below) and found that people who use drugs (as a group) administer far, far, far more naloxone than any other group of professionals charged with protecting the health and safety of the public.

Eliza Wheeler: The history of naloxone distribution in the United States

Just this month, Nancy D. Campbell released a long-awaited new book on the history of the U.S. opioid crisis, naloxone, and the harm reduction community’s organized response. Campbell, a social scientist, has followed up a series of excellent books on drug policy with what is essentially a history of the harm reduction community’s work to create programs and services informed and operated by the experiences of people who use drugs. OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose, “charts the emergence of naloxone as a technological fix for overdose and describes the remaking of overdose into an experience recognized as common, predictable, patterned―and, above all, preventable. Naloxone, which made resuscitation, rescue, and “reversal” after an overdose possible, became a tool for shifting law, policy, clinical medicine, and science toward harm reduction. Liberated from emergency room protocols and distributed in take-home kits to non-medical professionals, it also became a tool of empowerment. After recounting the prehistory of naloxone―the early treatment of OD as a problem of poisoning, the development of nalorphine (naloxone’s predecessor), the idea of “reanimatology”―Campbell describes how naloxone emerged as a tool of harm reduction.”

Nancy D. Campbell: OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose

Putting it Together: Best Practice Guidelines

A number of governmental and non-governmental organizations have created summary documents of the research that has emerged from the programs that Bigg designed and that operate along similar principles. Many studies have evaluated whether the prioritization of naloxone distribution directly to people who use drugs is truly effective at reducing overdose deaths at a community level. Several key summary documents have emerged in past years.

A 2018 report from the CDC reviews a set of evidence-based strategies for reducing overdose deaths. The report is designed as an instruction manual of sorts, meant to assist individuals working at the community-level with development of programs and policies. It reviews a set of programs to which there is a corresponding evidence-base, highlighting those programs and policies which are deemed to be most effective.

In 2019, the research organization RTI brought together a group of experts with experience operating overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs, or working in the broader overdose prevention field in another capacity. The intent: to create a document with guidelines that would help stakeholders understand what policies and principles are needed to operate a successful program that achieves its stated goals. {Full disclosure, I was one of the key informants or “experts” interviewed for this project.} The result is an excellent summary of the approaches used within strong and effective overdose prevention programs. Many organizations have attempted naloxone distribution in past years, with a wide range of stakeholder organizations working to improve access. Yet, experts in the report identify a number of programmatic requirements that can halt a program from being effective and essentially serve as barriers.

The inimitable national Harm Reduction Coalition designed a stepwise guide that is useful reading for those with the goal of eliminating overdose. This manual is designed to outline the process of developing and managing an Overdose Prevention and Education Program, with or without a take-home naloxone component. Overdose prevention work can be easily integrated into existing services and programs that work with people who use or are impacted by drugs, including shelter and supportive housing agencies, substance abuse treatment programs, parent and student groups, and by groups of people who use drugs outside of a program setting.

Harm Reduction Coalition: Overdose Prevention & Naloxone Manual

Bonus

Overdose prevention programs are at their most effective when they put naloxone directly into the hands of those who are most at risk of overdose: individuals who use heroin and illicit drugs that may be unknowingly contaminated with synthetic opioids (eg. fentanyl). The general goal of these programs is to blanket a community of drug users with naloxone. There is theoretically one distribution network that is most likely to permeate this network of individuals: people who sell illicit drugs. Reporting from Filter explores the ways in which public health programs can take advantage of these markets and distribution channels to ensure all individuals at-risk are armed with the overdose reversal agent.

An Important Statement from the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition regarding the Cedar Rapids Police Chief

As the 2020 legislative session begins, IHRC staff have been made aware by multiple legislators that we have been the subject of slander and misinformation at the hands of the Cedar Rapids Chief of Police, Wayne Jerman.

Specifically, multiple legislators have reported that Chief Jerman claims IHRC distributes “crack pipes” and “tells community members not to call 911 in the event of an overdose.” As a result of these lies, legislators now say they are disinclined to support bills legalizing syringe service programs in Iowa, and that this withdrawal of support involves lawmakers who were previously very supportive of this evidence based legislation in particular, and of the work of IHRC in general.

This news is deeply troubling to our organization, as both claims are unequivocally false. IHRC neither distributes crack pipes nor do we encourage individuals not to call 911. These statements are slanderous and harmful. Moreover, we are shocked and disappointed that an official charged with the public trust would fabricate information in order to sway the opinion of elected officials away from support of legislation that would serve only to save lives and prevent the spread of devastating and costly infections. In his role as the Cedar Rapids Police Chief and the Legislative Chair and Liaison of the Iowa Police Chiefs Association, Chief Jerman has been a vocal opponent of these programs and their legalization, despite the robust success of syringe service programs in nearly 40 states across the country. A policy disagreement, however misinformed, is an expected part of legislative advocacy. Spreading lies in the hopes of gaining political advantage is not.

Addressing the particular claims: First, we do not distribute pipes. Period. Full stop. While harm reduction programs work to reduce the transmission of infectious disease, there is relatively little evidence to suggest that infectious disease transmission is facilitated through the sharing of pipes. There is no language in the current syringe service program bill that would legalize the distribution of pipes through public health programs. There is zero evidence to suggest that our programs distribute pipes and anyone with even a cursory familiarity with our work would understand how ridiculous this allegation is.

For those who are curious about what services we do provide, we welcome individuals to contact us at hello@iowaharmreductioncoalition.org to arrange a tour of our offices. You may also visit our website, where we keep a complete description of the services we do provide: https://www.iowaharmreductioncoalition.org/services/

Second, IHRC is an organization led, in part, by physicians and physicians in training. As such, we strongly believe in working with community members to ensure that they receive medical care when necessary and when their consent is given. We take the hippocratic oath (to do no harm) seriously and work to provide services that are deeply ethical and in line with our sworn oath. We have never instructed community members not to call 911 in the event of an overdose. On the contrary, we instruct our clients to seek medical care following an overdose and educate them on the importance of receiving follow-up care. These written instructions, included in every overdose reversal kit we distribute, are available on our website as well: https://www.iowaharmreductioncoalition.org/overdose-education-naloxone-distribution/

Our commitment to health care partnership and navigation can be demonstrated in many components of our programming. This includes robust programming to link people into both healthcare and addiction treatment. Through our programs, we bring hundreds of individuals annually into emergency departments and clinical appointments. Our staff accompanies clients to begin medication assisted treatment, receive care for skin and soft tissue infections, enter the hospital for suicidal ideation or severe mental illness, and initiate treatment for hepatitis C, HIV, and more.

“IHRC is very disappointed to hear that a campaign of misinformation is being led by someone who has sworn to protect and serve our community,” said Dr. Joshua Radke, IHRC Medical Director. “As an evidence driven organization, we take seriously promoting efforts which serve our mission – to promote the health, safety, and dignity of our participants. The claims that were made do not align with this mission, and are therefore not part of our work. As IHRC’s Medical Director and as an emergency department physician, I am especially appalled by any allegation that we do not promote emergency medical response. IHRC will continue to promote science-based programs and policy and will offer services that align with our organization’s core goals and values.”

These lies harm our community members and undermine the trust elected officials place in physicians, public health experts, and researchers. In order to ensure that elected officials receive the best available information regarding science, medicine, and public health, it is critical that law enforcement leadership refrain from making baseless allegations and stick to the facts. While we do not expect everyone to appreciate the legislation to authorize needle exchange programs in Iowa, we do expect that discussions about it will be professional, ethical, and mature, while maintaining a spirit of cooperation and collegiality. We also wish to stress that we enjoy positive working relationships with many law enforcement officers around the state and nation and are deeply grateful for the service these individuals perform in our community. This statement should not be taken as a criticism of this professional community, but of the single actions of one bad actor.

We remain committed to advancing this legislation as we believe that all Iowans deserve to live a life free of HIV, liver failure (the impact of hepatitis C), and devastating infections of the blood and heart, all of which are easily preventable through syringe service programs. When it comes to the human impacts of syringe exchange, there is no debate: these programs save lives. We trust that community members and elected officials will continue to recognize this indisputable fact and choose to ignore this ill-informed and weak anti-Iowan propaganda.

The Consequence of a Single Story

On a gray Saturday morning wet with April snow, eight storytellers met in the IHRC offices. The stories they told were small in scale and personal, with great power to explain the mission of IHRC.

Everyone’s story is worth telling. That’s the fundamental truth of StoryCenter. For three decades, StoryCenter has been supporting organizations and individuals in using digital storytelling for reflection, education, and social change.

As a storyteller and facilitator, I’ve seen the StoryCenter model help people transform their most meaningful moments into powerful video stories. These stories empower tellers and engage viewers. The IHRC community is rich with stories that deserve to be heard. So last spring, researchers from the University of Iowa College of Public Health, the College of Education, and I ran the first digital storytelling workshop at IHRC.

Digital stories are three-minute videos with narration, photos, and artwork. They aim to capture some moment from our personal stories that can have a greater meaning and resonance.